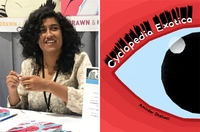

Cyclopedia Exotica

Aminder Dhaliwal. Drawn & Quarterly, $24.95 trade paper (268p) ISBN 978-1-77046-437-7

The opening pages of this graphic novel by Dhaliwal (Woman World) employ the rigid language of a fictional encyclopedia, sketching the history of cyclopes and their fluctuating relationship with the dominant “two eyes” culture. But as Dhaliwal arrives at the modern era—in which a cyclops sex icon Etna graces the cover of a pornographic magazine—the form falls away to loosely interconnected stories about cyclopes and their lives.

Stories, Etna tells us, can define us—whether it’s the one we tell ourselves, or the ones told about us. And the characters in Dhaliwal’s stories sparkle. They’re tenderly rendered and their problems are real. There’s Vy, a model who regrets being the face of a product that enforced false beauty standards; Bron, a self-hating cyclops haunted by a failed eye surgery; Pari, an anxious mother-to-be married to a two-eyed spouse; Pol, lonely and trying to date; and Jian and Grae, two artists trying to make their stamp on a two-eyed world.

Dhaliwal’s art is charming and expressive. Fans of Jillian Tamaki’s SuperMutant Magic Academy and Kate Beaton’s work will find much common ground here. Dhaliwal places funny, surprising details: one of my favorites involves a vintage breast separator—once meant to “normalize” the cyclops mono-breast—repurposed by young cyclopes as a BDSM device.

The struggle of the cyclops unfolds in metaphors for race, sexuality, gender, and disability, tangling with ideas about fetishization, interracial relationships, passing, and representation. But it also can slip, frustratingly, into didactic tendencies. For example, there’s a sharp send-up of the way publishing loves marginalized stories written by unmarginalized authors, which starts as an extremely good gag: an advertisement for a popular picture book Suzy’s One Eye, which allegedly captures “the voice of a young Cyclops girl in a Two-Eyed space,” is followed by a solemn photo of the (senior, two-eyed) author, “pictured at his private ranch where he resides alone.” But overexplaining undermines this point. Bron tries to write his own book, only to arrive back at the (very basic) plot of Suzy’s One Eye, and a section duplicating the full text of Suzy’s One Eye is far less effective than letting it serve as a textual McGuffin.

But despite these missteps, when it works, it works. I keep returning to Pari, who at one point puts on a very ugly dress. “I thought it would be cool to wear a dress designed by a cyclops,” she tells her husband, “I hate the dress but I want to support the existence of the dress.” I challenge any marginalized person to say that they haven’t had the exact same conversation about a book or film or television show created by someone with their shared identity—the overwhelming sense of responsibility placed on glass-ceiling breakers, yes, but also the desire to be seen as you truly are, and on your own terms. (Apr.)

Carmen Maria Machado is the author of In the Dream House, Her Body and Other Parties, and the graphic novel The Low, Low Woods.

Reviewed on: 01/14/2021

Genre: Comics