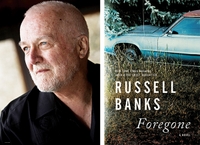

The Reserve

Russell Banks, . . Harper, $24.95 (287pp) ISBN 978-0-06-143025-1

Like Banks’s two most recent novels—

In a note that accompanies the advance reader’s copy of the book, Banks says he was drawn back imaginatively to the world of his parents. But this novel is not merely an homage to the class-riven universe of the Depression but also to the way it was portrayed in its own time. Some plot elements nod in the direction of Fitzgerald’s

Groves’s unrecognized conflicts are forced into consciousness through the agency of Vanessa Cole, the twice-divorced adopted daughter of one of the Reserve’s member families. Free of her last husband, a European nobleman whom she calls in her own mind Count No-Count, Vanessa is an alluring and determined seductress who sets her sights on Groves in the book’s initial chapter. Death, adultery and homicide follow, shattering each of the would-be lovers’ families.

This is a vividly imagined book. It has the romantic atmosphere of those great 1930s tales in film and prose, and it speeds the reader along from its first pages. In fact, Banks talents are so large—and the novel so fundamentally engaging—that it continued to pull me in even when, in its climactic moments, I could no longer comprehend why the characters were doing what they were doing. By then, the denouement has been determined largely by the literary expectations of a bygone era where character flaws require a tragic end. Despite that,

Reviewed on: 11/26/2007

Genre: Fiction

Compact Disc - 8 pages - 978-0-06-145751-7

Downloadable Audio - 978-0-06-162938-9

Downloadable Audio - 978-0-06-162940-2

Hardcover - 304 pages - 978-0-676-97972-5

Hardcover - 287 pages - 978-0-7475-9367-6

Open Ebook - 320 pages - 978-0-06-157287-6

Open Ebook - 978-0-307-36726-6

Open Ebook - 320 pages - 978-0-06-180958-3

Other - 320 pages - 978-0-06-157292-0

Paperback - 396 pages - 978-0-06-146902-2

Paperback - 320 pages - 978-0-06-143026-8

Paperback - 338 pages - 978-84-02-42057-2

Paperback - 304 pages - 978-0-676-97973-2

Peanut Press/Palm Reader - 320 pages - 978-0-06-157291-3