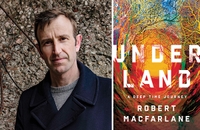

Mountains haven't always been viewed as magnificent tests of bravery or even as scenic vacation spots—only in the last few centuries have Westerners found them worthy of attention. As British writer Macfarlane (the London Review of Books; the Times Literary Supplement) points out, "until well into the 1700s, travelers who had to cross the Alpine passes often chose to be blindfolded," sparing themselves the terrors of the view. His point throughout this strangely compelling volume is that our attitudes toward mountains are very much a cultural product, a rich mix of theological, geological, artistic and social forces. With the development of geological science in the early 1800s, mountains, once viewed as "giant souvenirs of humanity's sinfulness," came to be seen as part of the earth's historical record. Recognized as "the great stone book" of history, mountains opened a window into "deep time," a glimpse of eternity. The thrill of vertigo, the infatuation with the unknown, the Social Darwinist challenge of the survival of the fittest, the march of British imperialism, even advances in cartography—all shaped the social imagination of mountains. As Western adventurers were increasingly lured from the Swiss Alps to the Himalayas, Macfarlane closes his study with the ill-fated Mallory expeditions to Everest, so mythic they almost defy analysis. The book itself is rather like some idiosyncratic, hand-drawn map of terra incognita. But for romantic, mountain-struck readers, Macfarlane's rich thoughts may make snow clouds clear, revealing new peaks and new wonders. B&w illus. Agent, Jessica Woollard. (June 3)

Forecast:This isn't white-knuckles, Jon Krakauer-esque adventure writing, but it should become a classic among mountain climbers.