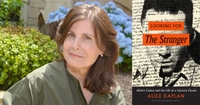

Less than 9% of American soldiers in Europe during WWII were African-American, but 55 out of 70 soldiers executed for crimes against civilians were black. That's prima facie evidence of racial injustice, but in this absorbing study historian Kaplan (whose The Collaborator

won the Los Angeles Times

Book Prize in 2001) digs beneath the statistics to explore how judicial bias operated on a practical level. She examines two court-martial cases held in France: James Hendricks, a black private hanged for killing a French farmer, and George Whittington, a white captain acquitted, on grounds of self-defense, of murdering a French commando. Both men apparently did kill their victims—and in Kaplan's view the incidents were the comparable doings of "two trigger-happy drunken soldiers"—but vastly different prejudices and privileges decided the defendants' fates. Hendricks was a truck driver in a segregated army who seemed, Kaplan contends, to embody his all-white jury's assumptions about black criminality, while Whittington was a well-connected officer and a decorated combat hero who was the picture of responsible white manhood. Kaplan supplements her own research with the perceptions of Louis Guilloux, a French intellectual who was an interpreter on both cases and wrote a novel about them. The result is a nuanced historical account that resonates with today's controversies over race and capital punishment (Sept.)