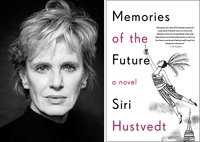

Novelist Hustvedt (The Sorrows of an American

) has been puzzling for years over the cause of her physical distress, from migraines to convulsions, and in this wide-ranging hodgepodge of technical jargon, research, memory and narrative, she tries to get at the root of what ails her. Since the death of her father some years before, the author has been beset by tremors, often before she has to speak publicly about him; she sensed that her shaking was hysterical, in the sense used by Freud, now called conversion disorder, a psychiatric illness whose manifestations often mimic neurological symptoms such as paralysis, seizures, blindness or deafness. Hustvedt immersed herself in the literature, visited psychiatrists and other specialists, volunteered to teach writing to psychiatric patients, tried antishaking medicine such as lorazepam, analyzed her dreams and submitted to tests like MRIs of brain and spine—all in order to try out “theories and thoughts that are built on various ways of seeing the world.” The more she delved, the more fractured the possibilities of explanation, as the self has many facets, conscious and otherwise, similar to the voices in a novel she might write. Indeed, Hustvedt's probing of the question “What happened to me?” taps at the source of the creative process, as such famous victims of migraine, epilepsy and bipolar disorder as Dostoyevski and Flaubert have documented. The barest of personal detail holds Hustvedt's narrative together, in favor of a dryly detailed academic treatise on etiology that is by turns elucidating and tedious. (Mar.)