A member of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone Indians of Nevada, Ned Blackhawk is a professor of history and American Studies at Yale University and the author of Violence over the Land: Indians and Empires in the early American West (2006). His next book, The Rediscovery of America: Native Peoples and the Unmaking of U.S. History, is forthcoming in April.

Ignored for generations, American Indian history has become among the most dynamic fields of U.S. historical inquiry, contributing significantly to the rise of settler colonial studies as well as global Indigenous history. As scholars now recognize, Indian peoples have fundamentally shaped and defined the North American past. From the founding of the first European settlements in North America to continuing debates over the meanings of American democracy, American Indian history remains integral to understandings of U.S. history and culture. Here are 10 essential titles from this burgeoning area of scholarly inquiry.

1. Like a Hurricane: The Indian Movement from Alcatraz to Wounded Knee by Paul Chaat Smith and Robert Allen Warrior

Few works in Native American history from the late 20th century carried a narrative commitment to exposing the ideas and lived experiences of Native American activists or treated contemporary Native Americans as determinative actors in modern politics. Smith and Warrior broke new ground, infusing their overview of the American Indian activist movement with interviews, in-depth biographical sketches, and passion.

2. Parading Through History: The Making of the Crow Nation in America, 1805–1935 by Frederick E. Hoxie

In one of the premier “reservation histories” ever authored, Hoxie offers a thorough, rich, and convincing examination of Crow history across the 19th and early 20th centuries. Among the most iconic of Plains Indian nations, the Crow struggled to retain autonomy over their reservation homeland during the trying economic, political, and religious ordeals unleashed by U.S. colonialism. Brilliant in its methodological depth and exposure, Hoxie’s study historicizes Crow adaptations and highlights a series of remarkable achievements, including the brilliant political careers of Plenty Coups, Robert Yellow Tail, and other Crow leaders.

3. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip's War by Lisa Brooks

Brook's account challenges the most storied (and studied) of all English colonies: Puritan New England. Tracing the lives of Indigenous leaders—most notably Weetamoo (Wampanaog) and James Printer (Nipmuc)—throughout the 17th century, Brooks uncovers an astonishing degree of cultural continuity in Northeastern Native kinship systems, gender relations, and land-use patterns. Deploying a rich archive and understanding of Algonquian placenames, she re-writes the familiar teleology of Puritan expansion and Indigenous decline, revealing how even after the cataclysmic revolution brought by King Philip’s War, Indigenous diplomacy, confederations, and survival characterized the Native Northeast.

4. The Indians’ New World: Catawbas and Their Neighbors from European Contact Through the Era of Removal by James H. Merrell

Adopting a centuries-long perspective, this regional history of Catawba ethnogenesis along the Carolina Piedmont began a profusion of scholarly studies that similarly chartered the place of “Indians and Empires” across the colonial world. Haunting in its recognition of the disruptions that preceded English settlement, Merrell’s account helped to unsettle familiar assumptions about the colonial world, exposing the centrality of violence, disease, and Indigenous enslavement to the making of the lower South.

5. The Great Power of Small Nations: Indigenous Diplomacy in the Gulf South by Elizabeth N. Ellis

With remarkable alacrity, Ellis extends the transformation of early American history currently underway and examines the adaptations, incorporations, and skillful diplomatic efforts of Louisiana’s petites nations, or small nations, who comprised the majority of French Louisiana. Painstaking in its reconstruction of 18th-century village life, The Great Power of Small Nations identifies how numerous migratory and refugee communities from eastern North America sought refuge within Mississippi Valley societies, thereby redefining the nature of Indigenous affairs across the sprawling French empire—North America’s largest colony until 1763.

6. The Sea Is My Country: The Maritime World of the Makahs by Joshua L. Reid

Reid explores the maritime history of the Pacific Northwest through the lens of the Makah Indian nation, whose reservation sits astride the tip of the Olympic Peninsula and has witnessed the only sanctioned whale hunts in modern U.S. history. As Reid outlines, whaling was enshrined into U.S. law in the 1855 Treaty of Neah Bay, a recognition of the essentialness of maritime economics and culture to Makah society and history. A detailed and suggestive study that includes beautiful artwork and an afterword by former Makah councilman and chairman Micah McCarty, this is Indigenous borderlands history at its best.

7. The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America by Andrés Reséndez

Few histories of American slavery mention the ubiquity of Indigenous captivity and enslavement. Fewer still track its development across the American continent. The Other Slavery tackles both and does so admirably. Largely rooted in the Spanish empire—the Caribbean, Mexico, and northern New Spain—Reséndez’s book also exposes the importance of Indian slavery, which potentially trafficked upwards of five million Indigenous laborers, as a key explanation for the demographic collapse of Indigenous populations.

8. Making Indian Law: The Hualapai Land Case and the Birth of Ethnohistory by Christian W. McMillen

Unlike other American minorities, Native nations retain unique legal powers under the U.S. Constitution. Unfortunately, few American educators know much about these distinctions or their significance to contemporary Native nations. Making Indian Law explores a particular area within federal Indian law—the emergence of the doctrine of “aboriginal title”—and does so in clear and effective ways. Focusing on how the Hualapai Nation of Arizona fought the expropriation of its land and resources, McMillen traces how a small number of tribal citizens organized themselves and eventually sought not only redress but also statutory remedies as their case reached the Supreme Court in 1941. In a unanimous decision handed down the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the court affirmed the tribe’s land rights and suggested the need for compensating them for their illegal seizure.

9. American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice by David E. Wilkins

The distinctiveness of Indian nations in modern American politics remains understudied and often misunderstood, with profound consequences for Indian communities. The collective works of David Wilkins offer the most sustained path through this thicket of problematics. Most notably, in American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court, he analyzes the emergence of various themes and precedents of federal Indian law and policy and also periodizes them, offering a critical overview of a series of constitutional concerns that have plagued tribal nations throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. With a depth of familiarity and engagement, this book offers a direly needed interpretive arc for gauging the faulty logics of Supreme Court rulings vis-à-vis Native nations.

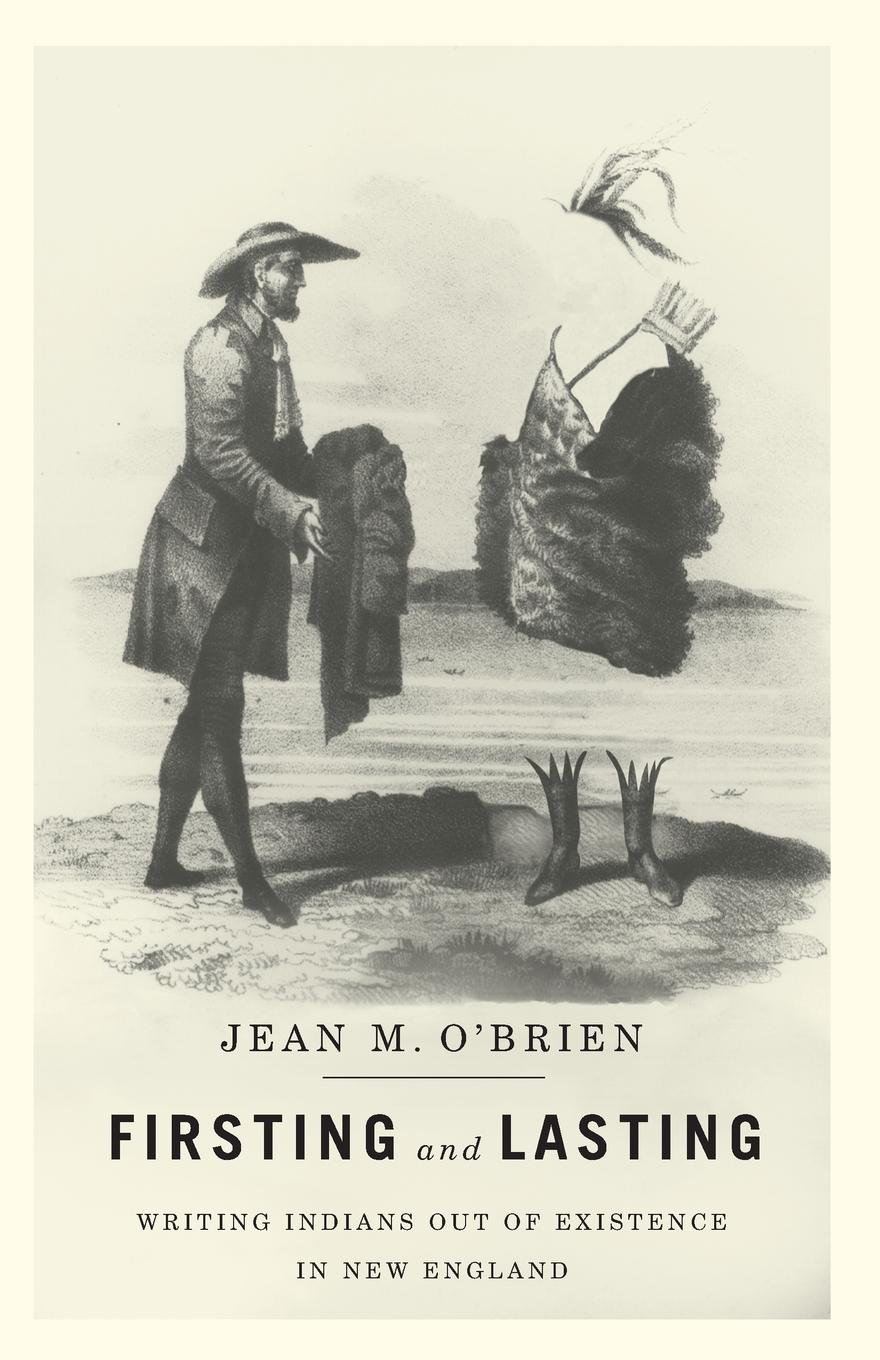

10. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England by Jean M. O’Brien

Despite being founded after Virginia and other French, Dutch, and Spanish colonies, New England, over time, came to be seen as the birthplace of American history due to its regional distinctions and attributes. O’Brien richly exposes the myriad ways that visions of Native peoples facilitated this regional distinctiveness, particularly in local histories in which Native peoples remained either the “first” or “last” members of their representative communities. Tracking such visions of alleged disappearance across hundreds of local histories, O’Brien identifies the production of historical knowledge itself as a constitutive element of settler colonialism.