This week: a forbidden book containing unsettling fairy tales, plus the uses and misuses of civil rights history.

The Hazel Wood

Alice Proserpine has grown up on the run, haunted by a book her mother, Ella, has forbidden her from reading: Tales from the Hinterland. It’s a collection of unsettling fairy tales written by a grandmother Alice has never met, a recluse with an obsessive fandom. Then Althea, the grandmother, dies, and Ella cryptically declares them free. Alice is focused on how they can turn their straw existence into a brick one after so many peripatetic years, and she’s bitterly disappointed with Ella’s solution: marry up. Shortly after, Ella goes missing, sending Alice and classmate Ellery Finch directly to the place Ella warned Alice to avoid: the Hazel Wood, Althea’s estate, where Alice painfully unravels the mystery of her childhood. Albert’s debut is rich with references to classic children’s literature; Alice’s sharp-edged narration and Althea’s terrifying fairy tales, interspersed throughout, build a tantalizing tale of secret histories and magic that carries costs and consequences. There is no happily-ever-after resolution except this: Alice’s hard-won right to be in charge of her own story. Ages 12–up.

Dreadful Young Ladies and Other Stories

The eight short stories and one novella in Newbery Medalist Barnhill’s collection are haunting and beautifully told. Each tale features characters, mostly girls and women, who chafe at rules and rebel in ways both quiet and extraordinary. The titular widow of “Mrs. Sorenson and the Sasquatch” dismays her neighbors by taking up with a huge furry humanoid. In “Elegy to Gabrielle—Patron Saint of Healers, Whores, and Righteous Thieves,” the young pirate Gabrielle Belain frees slaves and is defiant to the end. The poignant novella “The Unlicensed Magician” tells the story of a young woman, known as the Sparrow, as she quietly brings prosperity to her small town despite her country’s murderous dictator. Barnhill skillfully incorporates fairy tale elements and makes them freshly unsettling: many of her heroines have unusual effects on animals, and the title character of “Notes on the Untimely Death of Ronia Drake” faintly echoes Cinderella’s dead mother. Each story is written in intensely poetic language that can exult or disturb, sometimes within the same sentence, and evokes a dreamlike, enchanted mood that lingers in the reader’s mind. These tales are made to be reread and savored.

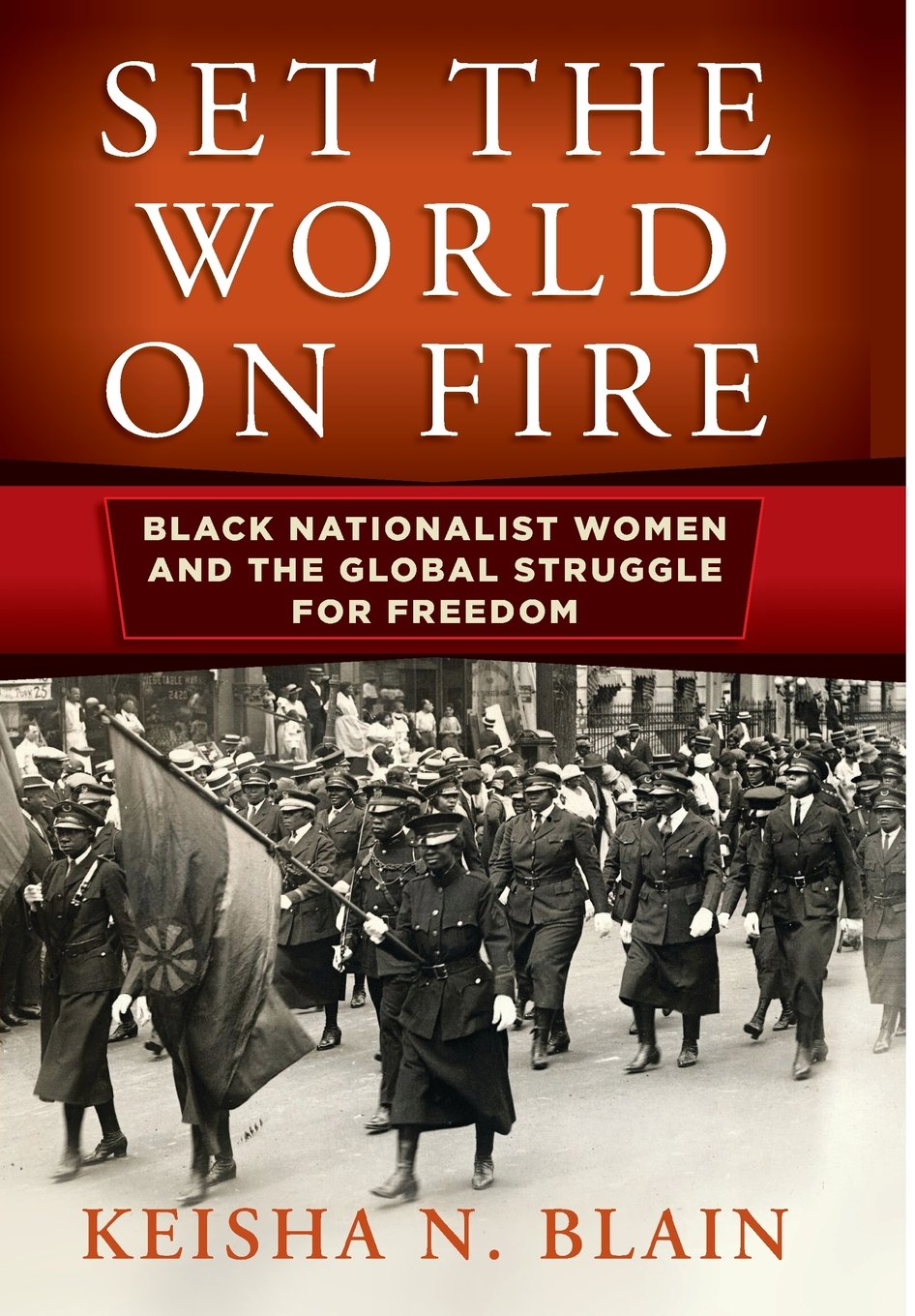

Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

Blain, assistant professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, illuminates an oft-ignored period of black nationalist and internationalist activism in the U.S.: the Great Depression, World War II, and early Cold War. Her engrossing study shows that much of this activism was led by African-American and Afro-Caribbean women. As racism intensified the sufferings of black Americans during the Depression, people of color in Africa and the Caribbean were increasingly agitated by British imperial rule; this circumstance encouraged female activists who had participated in Marcus Garvey’s movement to see the task of fighting white supremacy as one that united people of African descent across physical and political boundaries. Blain bolsters the roll of well-known black internationalists with less-familiar figures such as Chicago “street scholar” Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, who urged black Americans to emigrate to West Africa; Josephine Moody, who argued that black freedom could come only from the global overthrow of white power and urged African-Americans to “set the world on fire”; and Ethel Collins, who called on women to resist patriarchy within the black-nationalist movement. Adding essential chapters to the story of this movement, Blain expands current understanding of the central roles played by female activists at home and overseas.

The Journey of Little Charlie

Echoing themes found in Curtis’s Newbery Honor–winning Elijah of Buxton, this exceedingly tense novel set in 1858 provides a very different perspective on the business of catching runaway slaves. Eking out a living as South Carolina sharecroppers, the Bobo family knows hard luck. After 12-year-old Charlie’s father is killed in a freak accident, Charlie reluctantly agrees to pay off his father’s debt by accompanying a plantation overseer, the despicable Captain Buck, on a hunt for three runaways. Charlie’s journey takes him north to Detroit and Canada where black people and white people work and live peaceably together. Sickened by the dirty business of rounding up former enslaved men and women, Charlie hatches a risky scheme to steer them to safety. Curtis portrays Charlie as a product of his white Southern upbringing and values, skillfully conveying how his widening view of the world leads to a change in his thinking. Written in persuasive dialect and piloted by a hero who finds the courage to do what he knows is right, Curtis’s unsparing novel pulls no punches as it illuminates an ugly chapter of American history. Ages 9–12.

This Is What Happened

At the start of this beautifully written and ingeniously plotted standalone from Herron (Nobody Walks), 26-year-old mail room employee Maggie Barnes is trying hard not to get caught late one night in her 27-story London office building. Harvey Wells, an MI5 agent, has recruited her to upload some spyware on her company’s computer network from a flash drive. Adrift in the metropolis, Maggie has zero self-esteem and only the slimmest of personal ties to anyone, so this represents her chance to do something significant. Suffice it to say that her mission goes sideways. What at first appears to be a tale of spycraft and intrigue turns out to be something quite different—a disturbing portrait of contemporary England, with its “drip-drip-drip of sour resentment” (pre- and post-Brexit) and the palpable anomie of London. Most important is the fraught relationship between the pitiable Maggie and the manipulative Harvey, a man of great anger and bitterness. This dark thriller is rife with the deadpan wit and trenchant observation that Herron’s readers relish.

Tempest: Old West, Book 3

Legendary historical romance author Jenkins brilliantly touches on painful, significant historical and cultural references without dulling the shine of her inspiring, heartwarming third Old West romance (after Breathless), this one set in 19th-century Wyoming and starring two appealing African-American protagonists. Mail-order bride Regan Carmichael mistakes her intended, Dr. Colton Lee, for one of the bandits who’ve just attempted to rob her stagecoach, and shoots him in the arm. Widower Colton was looking for a mother for his daughter, not a love match. He was highly impressed by Regan’s letters and offered for her, but he had no idea she would be such a handful. At first, he doubts they’ll mesh well, but he quickly changes his mind when she wins over his daughter, his sister, and most of the other townsfolk. Regan longs for a loving marriage but accepts Colton’s statement that his heart will never be involved. She’s determined to be the best wife and mother she can be, and her selfless behavior and witty demeanor eventually bring Colton around. The story will evoke laughter, tears, and shivers of fear, and every word earns its keep. The amusing dialogue, lively characters, and vivid descriptions of the Old West make this even-paced romance a winner.

This Will Be My Undoing

Jerkins’s debut collection of essays forces readers to reckon with the humanity black women have consistently been denied. Her writing is personal, inviting, and fearless as she explores the racism and sexism black women face in America: “Blackness is a label that I do not have a choice in rejecting as long as systemic barriers exist in this country. But also, my blackness is an honor, and as long as I continue to live, I will always esteem it as such.” In her opening essay, Jerkins recounts the moment the division between black girls and white girls became clear to her, when she was told by a fellow black girl that “they don’t accept monkeys like you” after Jerkins failed to make the all-white cheerleading squad. This marks the first of many times that Jerkins asserts that a black woman’s survival depends on her ability to assimilate to white culture. A later essay addresses the paradox of the explicit sexualization of black women’s bodies and the cultural expectation that black women must be ashamed of their own sexuality in order to be taken seriously in a white world. At one point in the book, Jerkins lauds Beyoncé’s Lemonade as art that finally represents black women as entire, complex human beings. One could say the same about this gorgeous and powerful collection.

When Montezuma Met Cortés: The True Story of the Meeting That Changed History

Restall (The Conquistadors), director of Latin-American studies at Penn State, makes an impressive and nuanced case for why radically reinterpreting the Nov. 8, 1519, encounter between Spanish conquistador Hernando Cortés and Aztec emperor Montezuma leads to a totally different view of the following four centuries. “The Meeting,” as Restall dubs it, is the founding myth of Latin-American history, an event that inhabits the liminal space between history and legend. What is known about the meeting has been gleaned almost entirely from one source: 16th-century foot-soldier Bernal Díaz’s True History of New Spain, which Restall argues is neither true nor strictly historical. Using his knowledge of the Nahuatl language to revisit forgotten texts and parse eyewitness accounts of the Aztecs’ “surrender,” Restall strips away layers of accumulated historical sediment to reveal a meeting that looks very different from the version found in history textbooks and memorialized in the U.S. Capitol rotunda. According to Restall, the meeting wasn’t a turning point but rather merely one moment in the Spanish-Aztec War, a brutal two-year struggle historically whitewashed in favor of an account that justifies and reinforces the European presence in the Americas and became the foundation for a false history of indigenous weakness and European superiority. Blending erudition with enthusiasm, Restall has achieved a rare kind of work—serious scholarship that is impossible to put down.

The Invention of Ana

The spirit of Scheherazade is alive and well in Rosengaard’s debut novel about a woman named Ana Ivan, a survivor of Ceausescu’s Romania, who meets the unnamed Danish narrator on a Brooklyn rooftop and immediately launches into a story from her past. Right from the start, Ana captivates him with remarks about how she can travel in time or, as a child, was dead for two minutes, or how she is done with men. The narrator, it turns out, is a would-be writer, and Ana wants to use him to tell her stories, which, among other things, involve the suicide of her mathematician father and her investigation into his past to find out why he killed himself. The narrator’s Danish girlfriend, Laerke, arrives for a visit, but is surprised to find that he is distracted by Ana. The story culminates with Ana’s unusual art project, Timemachine, which the narrator becomes a part of. Ana makes for a maddening and beguiling presence throughout, as the author charts the emotional distance between Bucharest under Ceausescu’s despotic rule and present-day hipster Brooklyn, resulting in a striking, auspicious debut.

The Book of the Dead

This reissue of Rukeyser’s 1938 collection proves that the poem has lost none of its power––and, in fact, has gained resonance. Considered a foundational example of documentary poetry, it chronicles the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel disaster of 1931, in which hundreds of Union Carbide and Carbon workers were exposed to silica dust. It is estimated that 764 workers died of the lung disease silicosis, making it “the worst industrial disaster in U.S. history.” Rukeyser weaves together observations of her trip to West Virginia (“the most audacious landscape”), congressional testimony about the disaster, and workers’ conversations and letters, borrowing her title from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The poem is put in context with an extended introduction by Catherine Venable Moore, a West Virginia–based writer who lives five miles from where the disaster occurred. Moore gives valuable background about the tragedy––especially in fleshing out the racist elements of Union Carbide’s treatment of black miners––and adds lyrical, highly personal reflections on the evolving meaning of the poem. As Moore mulls the long history of environmental and health disasters that have befallen West Virginia, she notes how Rukeyser’s poem offers “a story of dignity and resistance that was yet to be told.” Innovative, gorgeous, and deeply moving, the work more than deserves a rereading: “planted in our flesh these valleys stand,/ everywhere we begin to know the illness,/ are forced up, and our times confirm us all.”

The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke

Stewart (Paul Robeson: Artist and Citizen) offers a detailed, definitive biography of Alain LeRoy Locke (1885–1954), the godfather of the Harlem Renaissance and all around “renaissance man in the finest sense... a man of sociology, art, philosophy, diplomacy, and the Black radical tradition.” A Harvard graduate with a Ph.D. in philosophy, Locke became the first black Rhodes Scholar, studying in England and Germany; Stewart chronicles those travels as well as Locke’s travels in Egypt, Haiti, and the Sudan. The book also explores Locke’s personal life as a gay man who was attracted to the young intellectuals who inspired him, including sculptor Richmond Barthé and poet Langston Hughes. Stewart details Locke’s misogyny toward writers Jessie Fauset and Zora Neale Hurston, as well as his complicated relationships with W.E.B. Du Bois and his Howard colleagues, who resented Locke’s influence. Stewart creates a poignant portrait of a formidable yet flawed genius who navigated the cultural boundaries and barriers of his time while nurturing an enduring African-American intellectual movement.

A More Beautiful and Terrible History: The Uses and Misuses of Civil Rights History

Theoharis (The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks), professor of political science at Brooklyn College, illuminates how the conventional wisdom about America’s civil rights story erases much of the movement’s radicalism and abounds in comforting clichés. She points out that by the mid-1980s the civil rights movement had become “a way for the nation to feel good about its progress.” Theoharis discusses how focusing on Southern desegregation ignores the physically and emotionally violent controversies that accompanied attempts at greater integration in supposedly liberal Northern cities such as Boston; similarly, depicting white Southerners as racist rednecks obscures the more genteel forms of discrimination practiced by people motivated by “indifference, fear, and personal comfort.” Rosa Parks is famous for having refused to give up her seat on a bus, but she and her fellow activists organized around much broader issues of social justice, many of which remain to be sufficiently addressed. Citizens and politicians of the 21st century revere Parks and Martin Luther King Jr. as heroes, yet many criticize Black Lives Matter activists as unworthy of their memory. Theoharis’s lucid and insightful study challenges that view, proffering a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the civil rights movement’s legacy, and showing how much remains to be done.