This week: how to stop time, plus how rivers made America.

Everything Happens for a Reason and Other Lies I’ve Loved

With grace, wisdom, and humor, Bowler (Blessed), a divinity professor at Duke University, tells of her cancer diagnosis and subsequent treatment in a way that pierces platitudes to showcase her resilience in the face of impending death. At 35 years old, after months of enduring stomach pains and visiting specialists who had conflicting suggestions, Bowler was rushed into emergency surgery for stage IV colon cancer. Surrounded by her husband, very young son, and a host of supportive friends, she faces down the likelihood that she will not live a year. As she responds well to treatment, she enters a period of uncertainty, hoping to survive and maximize her time with her family. Throughout her account of weekly flights to Atlanta from North Carolina for experimental therapy and realizations that each holiday might be her last, she relates her suddenly terrifying life to her academic work on the prosperity gospel—a peculiarly American belief in deserved success and control that is at odds with her current life. Bowler’s lovely prose and sharp wit capture her struggle to find continued joy after her diagnosis. This poignant look at the unpredictable promises of faith will amaze readers.

American Panda

Mei is only 17 and already a freshman at MIT, but her Taiwanese immigrant parents won’t be satisfied until she has a medical degree, a Taiwanese doctor husband, and children. To ensure the success of this plan, Mei’s mother monitors Mei’s behavior, calling constantly, nagging her to be more feminine, and engineering meet-ups with approved boys. But there’s so much her parents don’t know: the boy Mei likes is Japanese American, she’s too germophobic to be a doctor, and she’d rather be dancing. Worse, she’s in touch with the brother her parents disowned when he failed to meet family standards. Chao’s effervescent debut explores topics and themes that are salient for all teens—finding oneself and establishing an identity separate from one’s family—and perhaps even more so for children of immigrants, who have a foot in two cultures and an ever-present awareness of the sacrifices their parents have made. With sensitivity and an abundance of humor, Chao captures Mei’s growing realization that her desires are worth pursuing and the way that this discovery eventually brings Mei and her mother closer together. Ages 12–up.

Going for a Beer

Coover has been testing the limits of fiction for more than 50 years, and his interrogation of story structure and mingling of highbrow postmodernism with pop culture have influenced generations of writers. This collection celebrates Coover’s virtuosity as a short story writer; its 30 selected stories are playfully experimental, restlessly innovative, and a total joy to read. Of course there’s 1969’s classic “The Babysitter,” which famously assembles a kaleidoscopic range of possibilities faced by one teen during a night on the job, and reimaginings of stories from the Bible (“The Brother”), fairy tales (“The Dead Queen”), and film (“You Must Remember This”). But Coover’s genius is his ability to coax profundity from a story that begins, “The cartoon man drives his cartoon car into the cartoon town and runs over a real man,” or create dreamscapes, like the one built out of old celluloid in “The Phantom of the Movie Palace,” that come to seem more coherent in their peculiar logic than our own world. Readers will find the Pied Piper, Snow White, Punch and Judy, superheroes, stick men, a handsome Texas senator attempting to forestall a Martian invasion—and, in “Beginnings,” a writer who migrates to a distant island and shoots himself in the head before going on to enjoy his vacation because “It is important to begin when everything is already over.” This gets to the spirit of Coover’s work, the way it spikes traditional narrative with “spirals, revolutions, verb tenses, and game theory,” always imbued with humor, pathos, and wry intelligence. A career-topping marvel, this collection finds meaning in the wildness of the cultural subconscious.

The Source: How Rivers Made America and America Remade Its Rivers

Doyle, professor of river science and policy at Duke University, pays tribute to America’s waterways in this worthy history, noting their importance to the country’s development and its basic identity. Covering such topics as trade, politics, and environmentalism, Doyle looks at how the Erie Canal, for example, helped facilitate trade and commerce between the North Atlantic coast and the “burgeoning West.” The “once obscure towns” of Syracuse, Utica, Rochester, and Buffalo developed as “hubs of nineteenth-century manufacturing and industrialization,” while New York City became an entry point for European “immigrants heading toward America’s interior.” Doyle then turns his attention to the Mississippi River and the establishment of levee systems and flood controls along it. His discussions with Mississippi River towboat pilot Donnie Randleman and towboat captain Robert “Howdy” Duty add color and character to the narrative. Doyle rounds out this volume by examining ways in which Americans have altered rivers over the years. Gross and negligent pollution of industrial waterways—one result of which was that the Cuyahoga River in Ohio infamously burned in 1969—would eventually give rise to movements for river conservation and restoration. Doyle tackles the shifts in how America has viewed and used its extensive waterways, producing a comprehensive and enjoyable account.

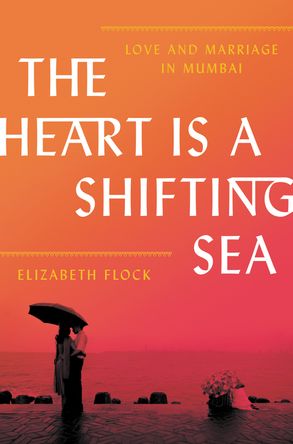

The Heart Is a Shifting Sea: Love and Marriage in Mumbai

Journalist Flock invites readers into the homes, lives, and marriages of three couples—one Marwari Hindu, one Sunni Muslim, and one Tamil Brahmin Hindu—living in Mumbai in this multifaceted portrait of love and marriage in modern India. Layered with history and glimpses of the varied cultures compressed into one vivacious city, the book pays as much attention to the lives of its subjects as it does to that which binds them together: the rituals of courtship and intricacies of marriage law, religious observances and festivals, and changing conventions that are seeing more couples choosing to live apart from their families and more women choosing to work outside of the home. Flock finds people trying to find happiness within the slipknot of tradition, longing for film-style romance within their arranged marriages, and searching peace with their lives inside a city and a country undergoing rapid population growth, Western influence, and rising far-right sentiment. There’s Ashok and Parvati, who get to know one another while planning a wedding (their courtship was arranged by their parents using an online matchmaking service); Shazhad and Sabeena, whose failure to conceive leads them to a more liberal practice of Islam (Sunni law doesn’t recognize adoption); and Maya and Veer, career-oriented individuals who deal with infidelity and Maya’s need for independence. Flock approaches the histories, hopes, dreams, and disappointments of her middle- and upper-middle-class couples as a reporter, not a storyteller, and the book is better for it, steering clear of caricature and sentiment, and letting each of her subjects emerge in the details of his or her own circumstances. Ostensibly a study of marriage as experienced by the people in it, Flock’s book also provides a vivid portrait of a nation in transition, through the lives and desires of its most progressive city’s residents.

How to Stop Time

Tom Hazard doesn’t age. Or, he does, but very, very slowly. He was born in France in 1581, but like other “albatrosses” (those who carry the burden of living forever), a century to him passes like a decade or less. In this enthralling quest through time, Haig (Reasons to Stay Alive) follows his protagonist through the Renaissance up to “now,” when Tom works as a history teacher in London. As Tom goes on various recruiting missions for the Albatross Society, the setting of the story moves from Shakespeare’s Globe to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Paris to Bisbee, Ariz., and other far reaches of the earth. The main rule of the Albatross Society is that, in order to stay protected from a group of scientists who want to study and confirm the existence of the albatrosses, an albatross cannot fall in love. And yet, all the while, Tom nurses a broken heart and searches for his long lost daughter, Marion, who is also an albatross. “Humans don’t learn from history” is one of the lessons Tom learns, and, despite everything he witnesses over the expansiveness of history, nothing can cure him of lovesickness. His persistence through the centuries shows us that the quality of time matters more than the quantity lived.

Asymmetry

Halliday, recipient of a 2017 Whiting Award, crafts a stellar and inventive debut, a puzzle of seemingly incongruous pieces that, in the end, fit together perfectly. In the early aughts, young NYC book editor Alice embarks on an affair with Ezra, a surprisingly kind older novelist. As the American military conflict in Iraq escalates, Alice and Ezra flit into and out of each other lives, bonding over the Red Sox, Scrabble, and Ezra’s failure to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. After a health scare lands Ezra in the hospital, Alice must decide the future of their relationship. The second, decidedly different section follows Amar, an Iraqi-American of complicated provenance who has been detained at Heathrow Airport on his way to Iraq. Alternating between the customs official’s curt interrogation of Amar and flashbacks to his life in America, the sequence draws the background violence of the earlier section violently into the foreground without sacrificing any of the former’s momentum or humor. A singular collision of forms, tones, and arguments, the novel provides frequent delights and never explains too much. Any reader who values innovative fiction should treasure this.

The Great Alone

Hannah’s vivid depiction of a struggling family begins as a young father and POW returns from Vietnam, suffering from PTSD. The Allbright family, barely making ends meet in 1974, moves from Seattle to the untamed wilderness of Kaneq, Alaska, to claim a parcel of land left to Ernt by a slain Army buddy. Together with his wife, Cora, who spurned her middle-class parents to marry him, and their 13-year-old daughter, Leni, who barely remembers the adoring dad who’s become so restless, Ernt is totally unprepared for the rigors of the family’s new home. Soon, his fragile mental health and his relentless abuse of Cora worsen during the long nights of the family’s first winter up north, even as the quirky and steely homesteaders around the Allbrights rally to help them. They intervene by forcing Ernt to leave in the winter to work on the newly started oil pipeline, but the added income and absences from Kaneq fail to fix his intractable paranoia and anger. Meanwhile, Leni finds friendship and love in a neighbor boy, Matthew, who is also a troubled survivor of a shattered family. Hannah skillfully situates the emotional family saga in the events and culture of the late ’70s—gas shortages, Watergate, Ted Bundy, Patty Hearst, and so on. But it’s her tautly drawn characters—Large Marge, Genny, Mad Earl, Tica, Tom—who contribute not only to Leni’s improbable survival but to her salvation amid her family’s tragedy.

All We Can Do Is Wait

Lawson’s empathetic, wrenching debut zeroes in on five teenagers from various demographics and family situations, who meet in the waiting room at Boston General Hospital, seeking news about whether their loved ones survived a bridge collapse. Chapters shift among Lawson’s complex and carefully drawn characters, offering distinct points of view and providing aching insight into the personal pain that colors their perspectives. For Alexa, a wealthy high achiever, the accident triggers guilt and rekindles an old grief; her brother, Jason—stoned, closeted, and miserable—suffers with guilt and grief of his own. Skyler, of Cambodian heritage, fears facing the world without her strong, dependable sister, and working-class Scott waits for information about the girl he loves. Meanwhile, Morgan deals with a private tragedy while the world focuses on the public catastrophe. Debut novelist Lawson, formerly of Gawker and current film critic at Vanity Fair, builds suspense as readers learn information the characters don’t know, while twists and revelations about the teenagers’ motivations for coming to the hospital result in a gripping and emotionally invigorating story. Ages 12–up.

Back Talk

Lazarin’s exceptional debut collection digs deep into the lives of women, telling complex stories of loss, hope, and joy. In “Hide and Seek,” a young mother aims to give her two daughters a happy childhood by moving them to the suburbs, only to discover the dangers that stretch into their new neighborhood. “Lovers’ Lookout” concerns a newly single woman in San Francisco, who meets a man while out on a run and toys with the idea of sleeping with him. “American Men in Paris I Did Not Love” takes a clever structure—each section focuses on one man who lusts after the story’s protagonist—to spin a tale detailing the strain of long-distance relationships. In “Floor Plans,” a friendship forms between two women as one tries to buy the other’s apartment, leading to a struggle for power. Equally effective are Lazarin’s narratives about adolescents. The title story, one of the collection’s shortest, powerfully conveys the experience of seeing a moment of youthful pleasure transform into a gossiped-about scarlet letter, while in “Gone,” two teens create a list of girls in their neighborhood who have died as they face their own struggles with boys and school. Lazarin’s work is confident and exhilarating; this auspicious collection is uniformly excellent.

The Seabird’s Cry: The Lives and Loves of the Planet’s Great Ocean Voyagers

In this moving exploration of 10 groups of seabirds, English writer Nicolson (Why Homer Matters) demonstrates that wonder about the natural world can be deepened by increasing one’s knowledge of it and that emotional wisdom can be reinforced by the acquisition of practical information. He blends insightful ethological observations with elements of the mythical and peppers his delivery of practical, premodern knowledge with poetic imagery. Nicolson paints the human-bird connection as intimate yet alien, writing of seabirds that their “gothic beauty is beyond touching distance” and a “miracle of otherness.” But he also immerses readers in the umwelt, or subjective world, of each bird without resorting to anthropomorphism, as when he describes the “odor landscape” that connects the shearwater to its phytoplankton food. Nicolson’s metaphorical language flows gracefully, with hints of the whimsical, and appeals to both the mind and the heart. While he takes ecological concerns seriously, his approach is as much a musing on the future as a call to action, placing humans in the role of participants in the natural world rather than in the roles of controllers or saviors. Nicolson combines a huge amount of scientific information with deeply emotional content and the net effect is moving and quietly profound.

Call Me Zebra

In Oloomi’s rich and delightful novel (after Fra Keeler), 22-year-old Zebra is the last in a long line of “Autodidacts, Anarchists, Atheists” exiled from early ’90s Iran. Years after her family’s harrowing escape, alone in New York after the death of her father (her mother died in their flight to the Kurdish border), Zebra decides to revisit some of the places where she has lived in an effort to both retrace her family’s dislocation and to compose a grand manifesto on the meaning of literature. Like Don Quixote, one of her favorite characters, Zebra’s perception of the world (and herself) is not as it appears to others, and her narration crackles throughout with wit and absurdity. As she treks across Catalonian Spain, she journeys through books and love affairs and philosophical tousles with Ludo Bembo, her also-displaced Italian foil. Their pattern of romantic coupling and intellectual uncoupling repeats itself; more interesting are Zebra’s other exploits—her strange and brilliant interpretations of art, her belief that her mother’s soul has been reincarnated inside a cockatoo, and the field-trip group she takes on pilgrimages to famous sites of exile. This is a sharp and genuinely fun picaresque, employing humor and poignancy side-by-side to tell an original and memorable story.

The Land Between Two Rivers: Writing in an Age of Refugees

Sleigh (Station Zed), a poet who teaches at Hunter College, takes the title of this beautiful collection from his essay about teaching poetry at universities in Iraq, but his theme is the transformational nature of poetry. Sleigh recounts his time working as a journalist in Jordan, Kenya, Lebanon, and Somalia. His stories from these war-torn places are sharply observed and humane, whether he is recording descriptions of what it is like to be processed into the massive refugee camp at Dadaab, Kenya, or to work in a sweets shop in Amman, Jordan, or relaying his own experience of watching a severely malnourished child become alert after eating a nutritional wafer in Mogadishu. But these stories are only one part of his project, which is to articulate how it is that poetry can capture what Seamus Heaney calls “the music of what happens,” the essence of direct lived experience. The second half of the book is a remarkable critical memoir, in which Sleigh writes perceptively about some of his poet heroes, including David Jones, Anna Akhmatova, and, most prominently, his lifelong friend Heaney. What emerges is a uniquely personal take on the responsibilities of the poet and the potential for language to be “a form of care.”

Virgin

Sotelo explores the power of mythologizing personal history in her striking debut, winner of the inaugural Jake Adam York Prize. The collection is divided into seven sections—Taste, Revelation, Humiliation, Pastoral, Myth, Parable, and Rest Cure—and from the start Sotelo cultivates intimacy through moments of vulnerability. For example, in “Summer Barbecue with Two Men,” she writes, “Tonight, the moon looks like Billie Holiday, trembling/ because there are problems other people have/ & now I have them, too.” Each section is loosely themed; for example, in “Humiliation,” Sotelo deals with shame in a variety of situations, while the poems in “Pastoral” revolve around issues with a father figure. Familiar figures from Greek myths—namely Persephone, Ariadne, and Theseus— are recurring symbols that serve as a means to probe the darker sides of human behavior. In “Death Wish,” Theseus battles suicidal ideation and is later seen “bleeding from/ his head to his hands,/ like Christ without clear cause.” In the subsequent poem, he declares, “I’m only good/ at killing what I know, then taking off.” The book is also replete with novel images, as when Sotelo describes a heart as “a lake where young geese// go missing, show up bloody// after midnight.” With humanity and raw honesty, Sotelo finds fresh ways to approach romance, family, and more.