This week: a history of the American heartland, plus Ian McEwan's new novel.

Wunderland

Epstein’s heartbreaking historical tour de force (after The Painter from Shanghai) juxtaposes Nazi-era Germany and 1980s New York City to devastating effect. The story opens in 1933: German schoolgirls Renate Bauer and Ilse von Fischer are best friends as Hitler comes to power and Jews become increasingly demonized. Renate is dating a young white supremacist and, along with Ilse, tries to join the Nazi-sponsored Bund Deutscher Madel. But after Renate discovers that her now-Christian father was born Jewish, Renate and her family are subjected to Gestapo questioning and blackmail. Ilse coldly drops her best friend, and, caught up in the growing nationalism, she betrays Renate’s family. In the East Village in 1989, Ava Fischer receives her estranged mother’s ashes and a sheaf of letters that outline her mother’s biggest regrets. She’s always felt unwanted by her mother, after being left for years in a German orphanage. But after she obtains the package, which contains a shocking secret about her parentage, everything suddenly makes a strange sort of sense. Epstein doesn’t stint on the horrifying details of the indignities dealt to Jews during Hitler’s reign. Man’s inhumanity to man—and the redemptive power of forgiveness—is on stark and effective display in Epstein’s gripping novel, a devastating tale bound for bestseller lists.

Flowers of Mold

The characters in this stellar collection from Ha, her American debut, live at the edge of normalcy, flirting with the strange and unsettling while going about their everyday routines. “The Woman Next Door” sees a mother slowly lose control of her family and short-term memory after befriending her new neighbor. “The Retreat” begins as a tale concerning commercial tenants rallying to stop their landlord from demolishing their building before evolving into a story of murder. In the harrowing “Nightmare,” a young woman believes she is a victim of a sexual assault, yet her parents try to convince her she dreamt the incident, and in the lighter “Early Beans,” a man agrees to deliver a package for an injured moped messenger and ventures into the unknown. Ha sets many of her narratives in the unbearable heat of spring and summer, which adds to the environment and engages the senses, so, for example, when the main character of the title story sifts through a woman’s trash, the odor of rotted food twists round his attempts to learn more about her. Likewise, in “Flag,” an electrical repairman battles the temperature as he uncovers the mystery of a local power outage. This impressive collection reveals Ha’s close attention to the eccentricities of life, and is sure to earn her a legion of new admirers.

Sisters and Rebels: A Struggle for the Soul of America

In this excellent triple biography, Hall (Like a Family) follows Elizabeth, Grace, and Katherine Lumpkin, whose lives and work touched many elements of 20th-century social history. They were born in late-19th-century Georgia, daughters of a Klansman who raised them to be persuasive orators at Confederate veterans’ reunions. Elizabeth (1888–1963) stayed true to the Lost Cause, even having a Confederate-themed wedding. Her progressive younger sisters, however, rebelled. Grace (1891–1980) and Katharine (1897–1988), influenced by liberal Christian denominations and women’s colleges, moved north and wrote in favor of equality for women and black people. Katharine earned a PhD in social work; in middle age, she wrote a landmark autobiography, The Making of a Southerner, and worked as a teacher and a journalist, often under FBI surveillance for her leftist leanings. Grace was a labor journalist and wrote fiction, but after her proletarian novel, To Make My Bread, was published in 1932, she slipped into poverty, ending up conservative, bitter, and begging back in the South. Hall alternates among the sisters’ stories, concentrating on Katharine and Grace and connecting them to broader elements of 20th-century America (including the Scottsboro Boys, mill strikes, Communism, world wars, Brown v. Board of Education, the FBI, the YWCA, and the ACLU). These admirably crafted biographies of the Lumpkins, their cohorts, and their causes opens a fascinating window on America’s social and intellectual history. Photos.

The Heartland: An American History

In this sophisticated, complex work, history professor Hoganson (Consumers’ Imperium) uses the history of Champaign County, Ill., to explore and question the American myth of its “heartland” as a safe, insulated, provincial place—“the quintessential home referenced by ‘homeland security.’” The first chapter shows how white settlers in 1700s and 1800s emphasized local settlement to justify taking land from the mobile Kickapoo population of Central Illinois. Hoganson uses the raising of cattle and hogs in Champaign to trace shifting borders on the North American continent in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Then she dismantles the myth of the isolationist heartland with an analysis of Champaign’s involvement with organizations such as the Inter-Parliamentary Union and the International Institute of Agriculture. And she flips the “flyover country” cliché, looking at how Champaign citizens are connected to the rest of the world by telegraph wires, the weather, migratory birds, and military planes. The final chapter follows the Kickapoo people’s experiences into the 20th century, demonstrating that, contrary to myth, nothing about the heartland’s geography makes it a safe place. Deeply researched with a well-proven argument, Hoganson’s book will attract many scholars as well as general readers who like innovative, challenging history.

Bitter

In 1934, the wealthy father of Gilda Meyer, the narrator of British author Jakobi’s engrossing first novel, pushes her at 17 into marrying Frank Goodman, a business associate of his more than twice her age. Gilda, a student at a Surrey boarding school where she’s ostracized because she’s a German Jew, feels unprepared for marriage. In 1939, she gives birth to a son, Reuben, but severe postpartum depression prevents her from bonding with him. At the center for European refugees where she gets a job teaching English, she falls madly in love with Leo Zubek, a teacher from Poland. After she tells Frank about Leo, he agrees to a divorce if she relinquishes full custody of Reuben. Over the years, her relationship with her son grows distant. After Reuben marries Alice, a non-Jew, in 1969, Gilda becomes unhealthy involved in their lives. She spies on the couple obsessively, even secretly entering their London home. An inadvertent remark by Gilda’s mother brings secrets to the surface, and Gilda realizes her life isn’t what she believed it to be. Gilda’s personal trials will keep readers in thrall to the bittersweet ending.

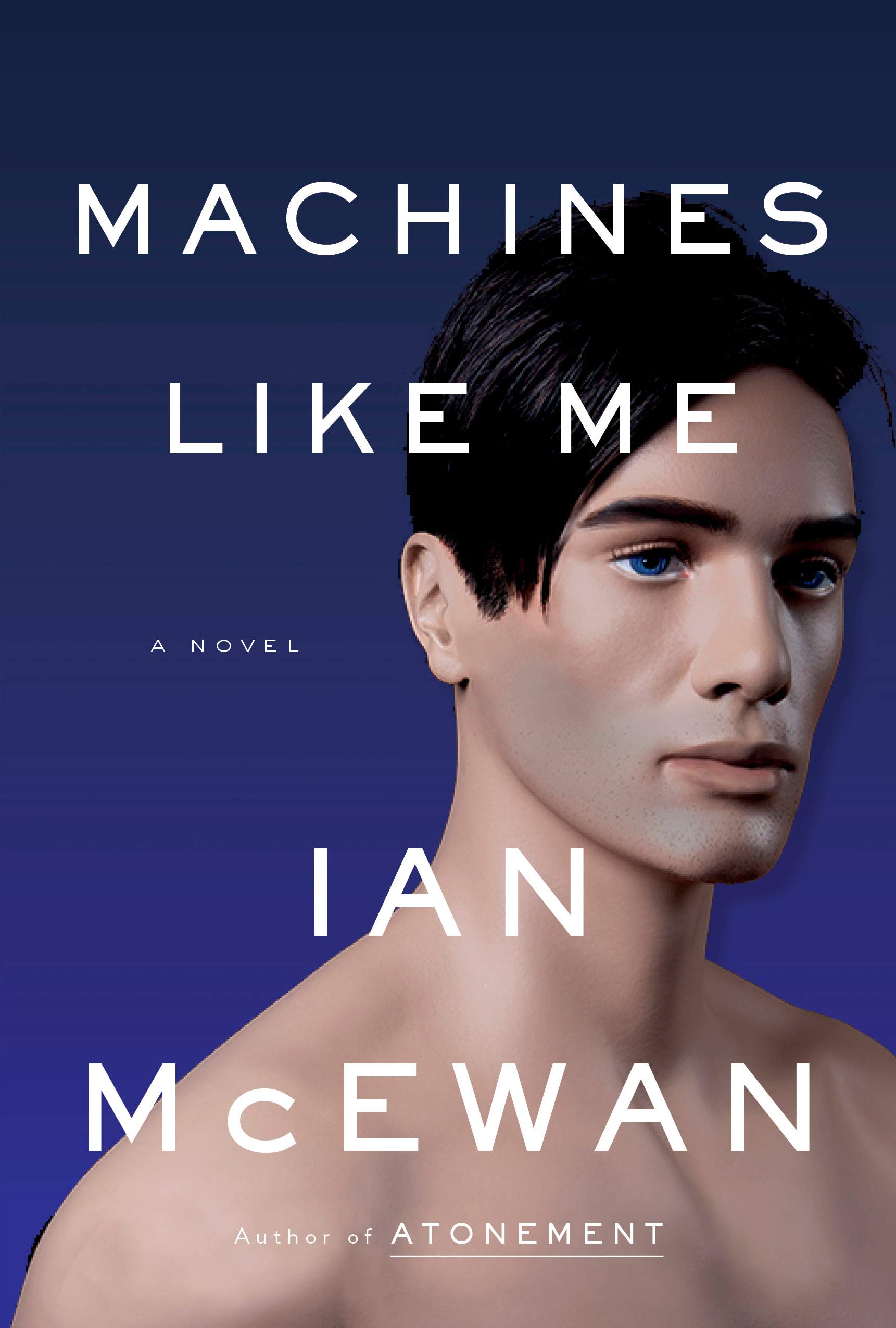

Machines Like Me

McEwan’s thought-provoking novel (after Nutshell) is about the increasingly fraught relationship between a man, a woman, and a synthetic human. Opening in an alternate 1982 London in which technology is not dissimilar from today’s (characters text and send emails), 32-year-old Charlie spends £86,000 of his inheritance on the “first truly viable manufactured human with plausible intelligence and looks,” who can pass for human unless closely inspected. His name is Adam (there are 12 Adams and 13 Eves total; the Eves sell out first), and Charlie designs Adam’s personality along with his neighbor and girlfriend Miranda. Soon, Adam informs Charlie that he “should be careful of trusting her completely,” and quickly falls in love with her, thus inextricably binding their fates together. The novel’s highlight is Adam, a consistently surprising character who quickly disables his own kill switch and composes an endless stream of haiku dedicated to Miranda because, as he states, “the lapidary haiku, the still, clear perception and celebration of things as they are, will be the only necessary form” as misunderstanding is eradicated in the future. The novel loses steam when Adam’s not the focus: much page space is devoted to a thread about an orphan boy, as well as Charlie’s thoughts and feelings about Miranda. Though the reader may wish for a tighter story, this is nonetheless an intriguing novel about humans, machines, and what constitutes a self.

Hawk Parable

In his 1950 Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Faulkner argued that under the sway of a “universal and physical fear,” writers had forgotten how to attend to “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself.” In her second book, Mills (Tongue Lyre) proves that Faulkner underestimated a poet’s ability to manage enormous shifts of scale. Questions probe and pierce: “Can I call it light/ knowing what came?” Mills unlooses documentary evidence of bomb testing, deployment, and devastation that intersect with moments of acute self-reckoning: “So I kissed a goat on the mouth. I was warned./ I looked too fast into its eyes, both/ black stitches.” Haunted by the unverified possibility of her fighter-pilot grandfather’s “involvement in the Nagasaki mission,” Mills scans skies for contrails, scrutinizes negatives, reads survivors’ accounts, and sifts through white sands: “I swallow vomit after watching// the island wart into an orange bulb,” but “Gone is the oyster-/ white rocket. You can’t/ take it back.” The poet asks: “Did the garble/ protect this body from history?” Her answer: “The land buries the thing we made to live/ just beyond the imagination.” Here, Mills has written a book for the long nuclear century.

Storm of Locusts

Roanhorse’s second Sixth World apocalyptic fantasy novel is less emotionally charged than its predecessor, Trail of Lightning, but dives deeply into the characters, introduces a great new one, and continues weaving Navajo beliefs overtly and subtly into the story. Maggie Hoskie, monsterslayer, learns that Kai, the powerful young medicine man she loves, may have been kidnapped by a cult leader with powers of his own. Maggie is forced to venture into the ravaged world beyond Dinétah, the Navajo’s protected land, to save both Kai and Dinétah itself. There’s plenty of tension, particularly with Maggie cut off from her homeland and trying hard to keep from killing anyone. She’s joined by teen girl Ben, who displays a perfect balance of strength and vulnerability, and her effect on the otherwise distant Maggie is a high point of the book. The depiction of North America in ruins is a dark treat, including vivid scenes of women saving enslaved women and supernatural locust swarms descending. Readers who enjoyed Roanhorse’s first book will eagerly blaze through her second.

Appendix Project: Talks and Essays

Presented as a series of appendices to novelist and memoirist Zambreno’s previous work, Book of Mutter, this collection of 11 talks and essays reveals her anew as a master of the experimental lyric essay. In an allusive, fluid style worthy of Susan Sontag or Virginia Woolf, Zambreno roves wildly over what seem disparate reference points, but never fails to center the essays around approachable themes—most prominently, her mother’s death, also the subject of Book of Mutter. In one entry, Zambreno blends critical theory, philosophy, and memoir, moving from analyses of paintings by On Kawara, to musings on how Roland Barthes captures the “looping character of mourning, as it attempts and fails to be rendered into language,” and on to experiences of new motherhood. In another piece initially devoted to her thoughts on turning 40, Zambreno ends by considering how to preserve one’s privacy even in personal writing, reflecting on why she omitted a revealing anecdote about her mother from Book of Mutter, but considered including a section about Marilyn Monroe’s death. For some, her book may seem esoteric and overly diffuse. But for most, the calm inquiry, wise voice, and poignant urgency behind every sentence will coalesce into a deeply reflective meditation on art, loss, and how “time makes the intensity of mourning pass—and yet, nothing is soothed.”