This week: new books from Attica Locke, Jacqueline Woodson, and more.

A Little Hatred

Abercrombie expands the First Law fantasy universe with a new epic saga of war and power set in a world where the industrial age is rising. Rikke’s Long Eye, a somewhat reliable prophet, foresees a battle in the North, but she doesn’t expect Northern warrior Stour Nightfall and his men to come looking for her. Luckily, she escapes, reuniting with her father, the Dogman; a friend, hotheaded Leo dan Brock; and Leo’s mother, Lady Governor. Together they fight for glory against superior Northern forces. Far away, Prince Orso is hungering for a cause, and when the Northern attacks worsen, he finds it. Without the funds for an expedition, he persuades Savine dan Glokta, his lover, to invest in his army so he can support the Dogman and the others. Meanwhile, rumblings of rebellion emerge as workers suffer. Business-savvy Savine sees an opportunity in the unrest—but when she travels to the industrial city Valbeck, revolutionaries seize control of the city, destroying factories and taking hostages. Orso and his new army are ordered to Valbeck to put down the insurrection, leaving the Dogman, Leo, and Lady Governor stranded and forced to make difficult choices. This isn’t a bad starting point for new readers, but returning fans will get the most out of it, as these characters are the heirs and descendants of the previous books’ protagonists. With expert craft, Abercrombie lays the groundwork for another thrilling trilogy.

Gamechanger

As this exuberant, exciting near-future yarn keeps reinventing itself, the action gets wilder and the scope wider, until the future of humankind is at stake. Though the Clawback project is beginning to rejuvenate an ecologically ruined Earth, public responsibilities are still unsettled and fluid. Cherub “Rubi” Whiting, a popular star of elaborate multiplayer virtual reality games, is excited to become a lawyer, but her first client, Luciano Pox, turns out to be difficult—and dangerous. Besides being an anti-restoration terrorist, Luciano could be a renegade AI, the dread superhuman Singularity, or an advance scout for an invasion fleet from Proxima Centauri. Meanwhile, Rubi’s father is on an obsessive hunt for the ancient oligarchs who survived Earth’s devastation and are plotting to grab power again, and Gimlet Barnes, Rubi’s rival and potential lover, is coping with her nine-year-old daughter going on a mission for the Department of Preadolescent Affairs. Each new chapter adds a different viewpoint and further information that upends reader expectations, stirring the plot in startling and wonderful ways. This delightful pinball machine of a book recalls the whiz-bang joy and gleeful innovation of Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash.

The Undying: A Meditation on Modern Illness

Poet Boyer (Garments Against Women) returns with a beautiful memoir about her battle with breast cancer. The book covers Boyer’s 2014 diagnosis at age 41, her grueling chemotherapy treatments, and her double mastectomy, delving into the fear, suffering, and loneliness that cancer brings. Cancer makes “the boundaries of our bodies break,” Boyer writes. “Everything we were supposed to keep inside of us now seems to fall out.... We can’t stop crying. We emit foul odors. We throw up.” Boyer criticizes the “capitalist medical universe” in which women are given “drive-through mastectomies,” and she puts into sharp focus the economic toll cancer takes on women of limited means. A single mother with no savings, Boyer had to return to her teaching job 10 days after her surgery because her medical leave had run out; she was so weak that friends had to carry her books. This memoir lays bare Boyer’s pain and exhaustion and is stacked with revelatory observations: “There is no more tragic piece of furniture than a bed,” she writes, “how it falls so quickly from the place we make love to the place we might die in.” Boyer’s gorgeous language elevates this artful, piercing narrative well above the average medical memoir.

Opioid, Indiana

The landscape of Middle America is grim but has glimmers of hope in this outstanding novel from Carr (Sip). Riggle, 17, is on the verge of adulthood and feels like a misfit in the rural Indiana town he has recently moved to from his native Texas. His parents dead, he lives with his young uncle Joe and Joe’s girlfriend, Peggy, more an object of lust to Riggle than a surrogate mom. Riggle’s suspension from school for vaping only amps up his aimlessness. He has one good friend, named Bennet, a fellow high school student and neighbor. They hang out, go to the movies together, and ponder their futures after the recent school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. Nostalgia about his mother’s omelets leads Riggle to a restaurant called Broth, where he finds a connection with the chef and almost lands a job. Joe is away from home, getting high—in fact, everyone around seems to get high—and the upcoming rent payment looms large. As Riggle’s week of suspension progresses, flashbacks reveal happier times during his childhood, and there’s an unexpected death, the possibility of new friends, and a threat from a local yokel at the other end of a gun. The first-person narration has authenticity and candor. Carr’s novel is both gripping and timely.

Gallows Court

In this exceptional series launch from Edgar–winner Edwards (Dancing for the Hangman) set in 1930 London, ambitious tabloid journalist Jacob Flint is hoping to make a name for himself by interviewing Rachel Savernake, a judge’s daughter, whose amateur detecting solved a murder that baffled Scotland Yard. Rachel had identified Claude Linacre, a prominent politician’s brother, as the killer shortly before Linacre fatally poisoned himself. After Rachel rebuffs Jacob’s inquiries about the Linacre case, she persuades a terminally ill banker and philanthropist to write a confession that he strangled and dismembered a nurse—and then shoot himself. Entries from an 11-year-old journal, written by someone whose role is initially unclear, accuse Rachel of being a murderer. More bloodshed follows as Jacob tries to figure out Rachel’s motives and culpability. The labyrinthine plot is one of Edwards’s best, and he does a masterly job of maintaining suspense, besides getting the reader to invest in the fate of the two main characters. Fans of Edgar Wallace’s classic Four Just Men won’t want to miss this one.

Think Black: A Memoir

In this powerful memoir, Ford (Whiskey Gulf) tells the story of his father’s tenure as IBM’s first black systems engineer. Though he was recruited in 1947 by the company’s founder, Thomas J. Watson Sr., John Stanley Ford endured 25 years of racism from his white coworkers, who repeatedly tried to get him fired. “Like [Jackie] Robinson, my father had also stepped into a role elevating him as a symbol much larger than his individual self,” Ford writes. Writing with a potent sense of outrage, Ford portrays his father as more conciliatory than he would have been when he himself was hired by IBM in 1971 and brought with him an African nationalist pride. Throughout, Ford details IBM’s racist history supporting both the Nazis and apartheid, and how his father, in his stoicism, fought back against the company’s racism (he obtained a document that contained answers to questions on IBM’s entry exam and gave it to black applicants). Ford came to see his father as a fighter who made his life as a black man better. “Whenever I hear the blips and beeps, the whines and whirs of a computer,” Ford writes, “I recall what I learned from my father about these machines, about being a man who’s Black, and about being first.” Ford’s thought-provoking narrative tells the story of African-American pride and perseverance.

The Paris Orphan

Lester (The Paris Seamstress) reveals secrets from a WWII romance in this rich and riveting novel. In 2004 France, Australian art handler D’Arcy Hallworth has been hired to pack up photographs at the French estate of Lieu de Reves for shipment to Australia for an exhibition. She meets American Josh Vaughn, the photographer’s agent, and discovers that her mother, Victorine, may be the little girl in some of the photos from the 1940s. Romance blossoms between D’Arcy and Josh as she seeks to uncover the truth behind her mother’s appearance in the photos. In a parallel 1942 narrative, Jessica May is a New York model whose stalled career leads her to become a photojournalist, working as a war correspondent in Europe. There she meets Dan Hallworth, a handsome, respected American officer. Lester’s novel is modeled after real-life characters and is imbued with realism, highlighting the horrors of WWII and the discrimination faced by female correspondents. Readers will become engrossed from the very first page as mystery and romance are expertly combined into one emotionally charged, unforgettable story.

Heaven, My Home

Edgar-winner Locke’s searing sequel to 2017’s Bluebird, Bluebird finds African-American Texas Ranger Darren Matthews reconciled with his wife, though to maintain their marriage, he has agreed to take a desk job at the Rangers’ Houston office, where he’s assigned to analyze digital surveillance data on his state’s chapter of the Aryan Brotherhood. Then nine-year-old Levi King, the son of Aryan Brotherhood of Texas captain Bill “Big Kill” King, disappears in Marion County, and Matthews returns to field duty. Meanwhile, Bill, who evaded justice for killing a black man but is serving 20 years in prison on drug charges, writes to the governor to request an exhaustive search for his son. Matthews’s boss, who’s seeking an indictment of the Brotherhood, including Bill, hopes that the search for Levi will yield information that can be used against his father—before the incoming Trump administration, with its lack of interest in pursuing white supremacists, takes power. Matthew’s legal jeopardy from a prior case hovers over the action, but Locke makes the complex backstory accessible. This one’s another Edgar contender.

Wildhood: The Epic Journey from Adolescence to Adulthood in Humans and Other Animals

Human teens have much in common with their counterparts throughout the animal kingdom—and those commonalities are eye-opening as described in the latest from biologist Natterson-Horowitz and science journalist Bowers (coauthors of Zoobiquity). They reveal how a wide variety of species, fruit flies and pumas alike, must negotiate four competencies while entering adulthood: safety, socialization, sex, and self-reliance. Readers follow Ursula, a king penguin; Shrink, a hyena; Salt, a humpback whale; and Slavc, a wolf, as they deal with sex, friendship, and parents. Cultural references pepper the narrative (Katniss Everdeen is used as an example of youthful survival skills) and lighten the mood (while “ABBA and the Bee Gees were on the Billboard Hot 100..., a young whale found her first love”). Harsh reality also plays a role: as with humans, the teens of other species can and do put themselves in peril (a biologist relates a rite of passage among California sea otters, of entering the great white–inhabited “triangle of death” off the coast). But this work is ultimately reassuring—as in its message that “the joys, the tragedies, [and] the passions” of adolescence are not senseless, but “make exquisite evolutionary sense”—and should appeal to anyone who’s ever raised an adolescent, human or otherwise.

The Secrets We Kept

Prescott’s triumphant debut offers a fresh perspective on women employed by the CIA during the 1950s and their role in disseminating into the Soviet Union copies of Dr. Zhivago, Boris Pasternak’s banned masterpiece. In 1956, American-born Irina Drozdova gets a job at the CIA ostensibly as a typist but is destined for fieldwork. Former OSS agent Sally Forrester trains Irina in spycraft. Meanwhile, inside the Soviet Union, Boris Pasternak’s lover, Olga Vsevolodovna, is interrogated about Pasternak’s work in progress, Dr. Zhivago. After three years in a prison camp, she reunites with Pasternak, who, unable to publish in the Soviet Union, entrusts his novel to an Italian publisher’s representative. Back in Washington, Irina, now engaged to a male agent but in love with Sally, seeks assignment overseas. Dressed as a nun, she places copies of Dr. Zhivago, printed in the original Russian for the CIA, into the hands of Soviet citizens visiting the Vienna World’s Fair. Through lucid images and vibrant storytelling, Prescott creates an edgy postfeminist vision of the Cold War, encompassing Sputnik to glasnost, typing pool to gulag, for a smart, lively page-turner. This debut shines as spy story, publication thriller, and historical romance with a twist.

Pittsburgh

Examining his mother and father’s broken relationship, Santoro (Pompeii) expands their story into a superb combination of family saga, coming-of-age memoir, and tribute to his hometown of Pittsburgh. Santoro’s parents currently work in the same Pittsburgh hospital, where “they pretend not to see each other.” Santoro delves into their 1960s courtship, uncovering their complicated relationships with their own parents and in-laws and exploring familial ties that both bind and chafe, including a moving tribute to family friend Denny, a bighearted man who “helped me see my parents as people.” When Santoro visits home during college, he hears new family narratives from both parents, including an affair his father had right before he was married. He describes how this happens whenever he returns: “These reveals year after year, every summer or Christmas, the story always changing.” Throughout, Pittsburgh is a character in itself, declining and renewing. Santoro’s in-the-moment sense memories of its streets and row houses are lovingly wrought in marker lines; by leaving the patched corrections on his illustrations visible, with tape and cut-outs, he underscores the sense that recollections and relationships are malleable, and there’s a sense of continuous construction, like in the city itself. He simultaneously pays tribute and bears witness in artful detail, creating an origin story sure to move many readers to reflect upon their own beginnings.

Snowflake, AZ

In a note to readers, Sedgwick (Saint Death) cites his own bout with a “disputed” chronic illness as an inspiration for this cautionary tale. Eighteen-year-old Ash is shocked to learn that his brother, Bly, has dropped out of the police academy in San Francisco. In search of answers, Ash follows him to Snowflake, Ariz., and discovers that Bly is sick with an environmental illness. He, like others suffering from various forms of chemical and/or electromagnetic sensitivities, has found refuge and camaraderie in the isolated town. When Ash also falls ill with the disease and joins the community, he learns firsthand what it is like to have an ailment that most of the public, including medical professionals, believe is “all in his head.” Throughout, Sedgwick offers musings by educated community members (including philosophy professor Mona, engineer Detlef, and cave-dwelling scientist Polleux) on a number of topics, for example epigenetics (how diseases, stress, and toxins can change genes) and the biological roots of kindness. Framed as a memoir narrated by a much older, wiser Ash, this raw, deeply philosophical tale leaves readers with a timely, sobering message about how humankind’s treatment of the environment impacts the environment’s treatment of humankind. Ages 13–up.

Guts

With disarming candor and in her now instantly recognizable panel artwork, Eisner Award–winner Telgemeier weaves a tangle of personal preadolescent traumas into another compelling graphic memoir. A bout of stomach flu and some unpleasant encounters with food create in young Raina’s mind a swirling miasma of fear that she’ll throw up. This anxiety blights her school days (she freezes during a class presentation with her best friend and lashes out at a bullying schoolmate) and extends into fears about sickness and schoolwork, and frustrations with her raucous household. Telgemeier frames the girl’s panic attacks accessibly as sickly circles of green crowded with big, blocky words (“pain drowning choking death bad at math”). Raina’s parents take her to see therapist Lauren, who helps her to ground her fears and gain enough emotional strength to reconcile herself to changing friend dynamics, and an IBS diagnosis clarifies the way that mind and body can intertwine. Moments of elementary school drama are portrayed with credibility, and the story both normalizes therapy and shows a child developing useful coping mechanisms for anxiety in a way that will reassure, even inspire, readers. Ages 8–12.

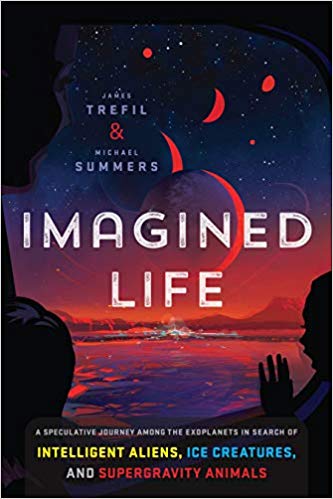

Imagined Life: A Speculative Journey Among the Exoplanets in Search of Intelligent Aliens, Ice Creatures, and Supergravity Animals

Posing a far-reaching question—what will alien life look like when humankind finds it?—the coauthors of Exoplanets explore possible answers in this lively, imaginative, and accessible look at cutting-edge exobiology. The first step for physicist/science writer Trefil, and Summers, a member of NASA’s New Horizon mission, is deciding how to define life. The basic definitions are broad, selected to cover every possibility imaginable so far. Next, the authors explore the clues, or “biomarkers,” that hint that a planet does—or did—harbor life. With those basics down, the book ranges widely, exploring an exotic variety of hypothetical life that might evolve on everything from Earthlike “Goldilocks” worlds with some surface water, to stormy, entirely water-covered worlds or dark “rogue” planets adrift in space with no home star. The discussion closes with a look at some really alien possibilities—life evolving in methane or ammonia instead of water, or inorganic life based on metals instead of carbon. Throughout, the spirited, nontechnical discussion is detailed enough to fascinate nonspecialist readers without overwhelming them. This is a marvelous introduction to a field fueled by both imagination and science.

Red at the Bone

Woodson’s beautifully imagined novel (her first novel for adults since 2016’s Another Brooklyn) explores the ways an unplanned pregnancy changes two families. The narrative opens in the spring of 2001, at the coming-of-age party that 16-year-old Melody’s grandparents host for her at their Brooklyn brownstone. A family ritual adapted from cotillion tradition, the event ushers Melody into adulthood as an orchestra plays Prince and her “court” dances around her. Amid the festivity, Melody and her family—her unmarried parents, Iris and Aubrey, and her maternal grandparents, Sabe and Sammy “Po’Boy” Simmons, think of both past and future, delving into extended flashbacks that comprise most of the text. Sabe is proud of the education and affluence she has achieved, but she remains haunted by stories of her family’s losses in the fires of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre. The discovery that her daughter, Iris, was pregnant at 15 filled her with shame, rage, and panic. After the birth of Melody, Iris, uninterested in marrying mail-room clerk Aubrey, pined for the freedom that her pregnancy curtailed. Leaving Melody to be raised by Aubrey, Sabe, and Po’Boy, she departed for Oberlin College in the early ’90s and, later, to a Manhattan apartment that her daughter is invited to visit but not to see as home. Their relationship is strained as Melody dons the coming-out dress her mother would have worn if she hadn’t been pregnant with Melody. Woodson’s nuanced voice evokes the complexities of race, class, religion, and sexuality in fluid prose and a series of telling details. This is a wise, powerful, and compassionate novel.