Martin Seay's debut novel, The Mirror Thief, is a true delight in the Cloud Atlas mold: a time-jumping epic that's part ominous modern thriller, part supernatural mystery, part enchanting historical adventure. Seay, whose book clocks in at 592 pages, picks 10 other long books worth the investment.

It seems that I have written a long novel.

People regard this as something worthy of comment, and I get that. During the years I was working on it, when I’d report my expanding page-count to friends, their reactions were often strikingly similar to ones I once got by announcing my plan to drive a twelve-year-old Hyundai Elantra from Cape Cod to the Pacific Northwest: surprise, doubt, concern. (“Really? Oh man. Good luck with that.”)

Maybe it’s just because I misspent my junior-high years plowing through the orientalist doorstoppers of James Clavell, but 600 pages doesn’t seem all that long, particularly for a novel like mine, with plotlines unspooling in different times and places. I think it’s possible to make too much of the wow-that’s-a-long-book phenomenon; we’ve all encountered hulking bricks that we zip through in a few underslept days, as well as wispy volumes that turn out to be dwarf-star dense. Successful books take the space they need.

In fact, every era provides examples of novels that succeed commercially and/or artistically despite—no, because of!—their girth. What follows is my list of the best of the bunch. The usual list disclaimer applies doubly here: I can’t claim to have made a complete survey of the field, because these books are long, y’all, and I’m only one man. (A note on terminology: I have defined “long novel” as “longer than mine.”)

1. The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (c. 1000, 1216 pages in Penguin Classics trade paperback edition, trans. by Royall Tyler)

Although its thousand-year-old original text is all but incomprehensible to present-day readers of Japanese, this sprawling tale of a nobleman’s loves and fortunes is the earliest work of literature that feels like a novel, less concerned with relating events than depicting its characters’ relationships, attitudes, and impulses. Most notably, Genji feels written in a way that the bard-sung epics of early Europe just don’t: We sense the author making discoveries about her characters through the process of inventing them, and letting the work take shape accordingly.

2. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale by Herman Melville (1851, 720 pages in Penguin Classics trade paperback edition)

Moby-Dick’s status as a “classic,” though certainly deserved, tends to obscure what a strange, profound, troublesome, and completely nutty book it is. By using one artificial, precariously-constructed reality (i.e. the form of the novel) to depict another one (i.e. life aboard a whaling ship), Melville sets out to explore fundamental questions about the nature of the world and our places in it, and to do so with humor, humility, and wonder that remain deeply affecting. By a substantial margin the best book of any kind ever written.

3. Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871–1872, 880 pages in Penguin Classics trade paperback edition)

The elasticity of the novel allows it to mirror our experience of living, expanding to follow characters across decades and to capture whole communities. Of course, readers (particularly male readers) are not always willing to grant writers (particularly female writers) the authority to paint on such broad canvases, which is one reason Marian Evans chose to publish her novels as George Eliot. Middlemarch—which tracks idealistic young Dorothea Brooke and ambitious physician Tertius Lydgate as they make ill-considered marriages in a scandal-prone English manufacturing town—takes on the sweeping scope, complex politics, and historical specificity that define its French Realist predecessors, while adding a psychological acuity that anticipates Henry James.

4. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1873–1878, 864 pages in Penguin Classics trade paperback edition, trans. by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky)

A near-contemporary of Middlemarch, Anna Karenina also traces the parallel paths of two characters, in this case Tolstoy’s fictional alter ego Konstanin Levin and the doomed socialite of the book’s title. The concerns in Karenina, however, are less social than existential, demonstrating that ultimate questions can be encountered in drawing rooms as freely as on whaling ships. Aspiring writers can learn almost everything they need to know about managing distance in narration—which is almost everything they need to know, period—through the careful study of the novel’s famous opening paragraphs.

5. The Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing (1962, 688 pages in Harper Perennial Modern Classics trade paperback edition)

Length also gives the novelist the opportunity to work in modules: to create seemingly independent books-within-books. This technique can come off as clever; in The Golden Notebook Lessing deploys it with painful urgency, shuffling her main narrative with ostensible diary excerpts that evoke the all-but-irreconcilable strands of a frustrated novelist’s consciousness: her past, her politics, her relationships, her dreams. The strange and powerful result is a work that seems to include a record of the labors that produced it, dragging the relics of its own creation into the light.

6. The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami (1994, 607 pages in Vintage International trade paperback edition, trans. by Jay Rubin)

Not Murakami’s longest novel, but probably his most effective. It amplifies the dreamlike atmosphere and offbeat interior logic of the briefer early works that made his global reputation, but also pushes into more challenging moral territory, tempering cool disdain for politics with a newfound concern with repressed historical burdens of trauma and guilt. Suggestive of a conspiracy thriller directed by David Lynch, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle somehow manages to be emotionally satisfying without ever quite making sense.

7. Turn of the Century by Kurt Andersen (1999, 672 pages in Random House trade paperback edition)

If you want your novel to be perennially hailed as a prophetic cultural critique, it’s probably a bad move to set it only one year in the future: reality will have caught up with it by the time it hits paperback. And yet Andersen’s 1999 book—set, as the title suggests, in 2000—still reads surprisingly well, holding its own among more-lauded zeitgeist-snapshots like Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections: somewhat less sweeping and artful, but admirably sharp and far-sighted in its depiction of the ways people are subtly warped by the technologies they adopt.

8. House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski (2000, 709 pages in Pantheon trade paperback edition)

Something else that really long books do is force us to contend with them as objects: to be attentive to the physical experience of reading them. I have a vivid tactile memory of my first encounter with House of Leaves, which I discovered on a table in the bookstore where I worked, looming like the telephone directory for Hell. While Danielewski’s debut novel is many things—a cult phenomenon, a horror yarn, a love story, a greatest-hits compilation of every postmodern narrative device you can think of—it is first and foremost an artifact: a typographical labyrinth that you read with your body as much as your brain.

9. Skippy Dies by Paul Murray (2010, 661 pages in Faber and Faber trade paperback edition)

He certainly does—die, that is—in the midst of a doughnut-eating contest in the novel’s opening pages; the story then rewinds to show us exactly what brought young Skippy to this undignified end, and by the time we return to the incident 450-ish pages later, what was ridiculous has become devastating. An intricately-constructed epic set in an Irish boarding school and partaking energetically of discourses that range from poetry and physics to pop music and text messages, Murray’s novel is a fierce, funny, ultimately crushing indictment of the willingness of institutions to devour those whom they’re meant to protect.

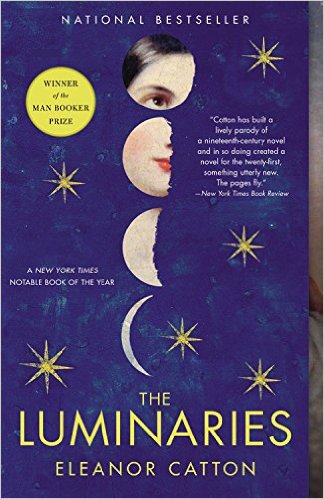

10. The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton (2013, 864 pages in Back Bay Books trade paperback edition)

Animated to a greater extent than any other novel in recent memory with the sheer pleasure of invention, The Luminaries is (at least superficially) a murder mystery set in a New Zealand gold-rush town in 1866, written in a style that recalls Victorian-era masterpieces by Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins. It is also composed according to an astrological scheme of daunting and beautiful complexity, which shapes the nature, behavior, and interactions of Catton’s characters. Reading it gives the exhilarating sense of a novelist in total control, fearlessly allowing the system she’s designed to deliver the full measure of wonder that it contains.