This week: what if there were a machine that could reveal your deepest secret? Plus: a definitive Thoreau biography.

The Late Show

The title of this excellent series launch from bestseller Connelly (The Wrong Side of Goodbye and 20 other Harry Bosch novels) refers to the midnight shift at LAPD’s Hollywood Division. Det. Renée Ballard has landed there in retribution for filing sexual harassment charges against her former boss, Lt. Robert Olivas. Two major crimes soon concern Ballard: the vicious beating of a woman, who says she was assaulted in the “upside-down house” but passes out before she can explain, and a nightclub shooting that kills five people. Though most “late show” cops hand off cases to their day shift counterparts, Ballard personally investigates the assault (with official approval) and the nightclub shooting (without). Olivas, who’s leading the latter investigation, wants her nowhere near the case. What follows is classic Connelly: a master class of LAPD internal politics and culture, good old-fashioned detective work, and state-of-the-art forensic science—plus a protagonist who’s smart, relentless, and reflective. Talking about the perpetrator of the assault, Ballard says, “This is big evil out there.” That’s Connelly’s great theme, and, once again, he delivers.

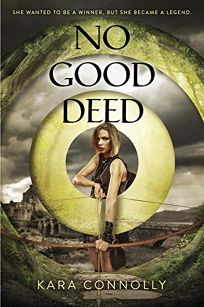

No Good Deed

The Epiphany Machine

Gerrard’s (Short Century) superb second novel has an exhilarating premise: what if there were a machine that could reveal your deepest secret—the uncomfortable truth about yourself you choose to overlook—by tattooing it on your forearm? The novel is composed of rules about the machine, testimonials, descriptions of quasiprophetic operator Adam Lyons, and excerpts from books by the mysterious Steven Merdula about the machine—but primarily the book is Venter Lowood’s memoir about coming of age in New York at the turn of the 21st century. Lowood contemplates and discusses American political history from the American Revolution to the War on Terror, raising questions about privacy, destiny, responsibility, and truth. Gerrard’s deft command of character, humor, and metaphor keep this intricate, philosophical novel fast-moving, poignant, and fun. In snarky banter, Venter and his best friend Ismail Ahmed communicate their deep affection and their playful rivalry, and in Venter’s tense conversations with his father (whose forearm reads “SHOULD NEVER BECOME A FATHER”) readers can see the painful legacy of the Lowoods’ encounters with Lyons and the machine. The figurative language is inventive and insightful: “Life is an extended freefall. An epiphany may help you see better.... Rather than a meaningless blur, you will see rocks and trees and lizards. An epiphany is not a parachute.” This is a wildly charming, morally serious bildungsroman with the rare potential to change the way readers think.

Ants Among Elephants: An Untouchable Family and the Making of Modern India

In this brilliant debut, Gidla documents the story of her resilient family and India’s modern political history. Gidla grew up in India as an untouchable, the lowest category in India’s caste system, and now works as a subway conductor in New York City. In this epic, she shares intimate stories of her uncle Satyam, a revolutionary poet and steadfast communist; her uncle Carey, a hapless yet ardent supporter of Satyam; and her mother Manjula, the core of the family’s strength. Her uncle Satyam was a political organizer within the movement that won its demand for statehood for Andhra Pradesh from former president Nehru. Gidla eloquently weaves together her family narratives with Indian politics, specifically focusing on the practices and consequences of caste inequality. The book is also a fascinating chronicle of the corruption within and political battles between India’s Congress Party and its Communist Party. Gidla is a smart and deeply sympathetic narrator who tells the lesser known history of India’s modern communist movement. The book never flags, whether covering Satyam’s political awakening as a young and poor bohemian or Manjula’s rocky marriage to a mercurial and violent man. Gidla writes about the heavy topics of poverty, caste and gender inequality, and political corruption with grace and wit. Gidla’s work is an essential contribution to contemporary Indian literature.

Less

In Greer’s wistful new novel, a middle-aged writer accepts literary invitations around the world—making his way from San Francisco to New York, Mexico, Italy, Germany, Morocco, India, and Japan—so that he will have an excuse not to attend the wedding of a long-time lover. Arthur Less is not known primarily for his own work but for his lengthy romantic association with a Pulitzer Prize–winning author, an older man who was married to a woman when their liaison began, and he believes himself to be the butt of many cosmic jokes and that he is “less than” in most equations. This is partially proven true, but not entirely. And even in Less’s mediocrity, when aided by a certain amount of serendipity (and displayed by the author with ironic humor), he affects people. Greer (The Confessions of Max Tivoli), an O’Henry-winning author, writes beautifully, but his occasionally Faulknerian sentences are unnecessary. He is entirely successful, though, in the authorial sleights of hand that make the narrator fade into the background—only to have an identity revealed at the end in a wonderful surprise.

Soul Cage

The discovery of a severed hand inside a sealed plastic bag in an illegally parked minivan propels Honda’s excellent second mystery featuring Lt. Reiko Himekawa of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police’s homicide unit (after 2016’s The Silent Dead). The vehicle was reported missing, by 20-year-old Kosuke Mishima, from a garage rented by his employer, Kenichi Takaoka of Takaoka Construction. A large pool of blood was on the garage floor. Mishima notified the authorities only after he was unable to reach his boss by phone. When the DNA from the hand and the pool of blood match, the police proceed on the theory that Takaoka was murdered. Though Mishima’s new girlfriend, whom he met about a month earlier, provides him with an alibi, Reiko is intrigued to learn of an unusual coincidence: both Mishima’s and his girlfriend’s fathers died in construction accidents. Honda heightens suspense by leaving the reader to wonder how that revelation connects with the novel’s cryptic prologue; the ultimate answer to this clever blend of procedural and whodunit doesn’t disappoint.

The Dark Dark

In her first collection, Hunt (Mr. Splitfoot) explores various relationships between women and men; the dead and the undead (literally and metaphorically); and lust, longing, and loneliness in 10 stories designed to jolt and beguile. In “Cortés the Killer,” a brother and sister witness the gruesome death of their horse during a Thanksgiving outing to Walmart. It sparks questions about their father’s death from lung cancer. In “Love Machine,” an FBI agent falls in love with the robot he designed to take out Ted Kaczynski. An extramarital tryst between two strangers opens a loophole and brings a seemingly dead dog back to life in “The Yellow.” In “Wampum,” a mother’s ex-boyfriend seduces her precocious 14-year-old daughter, or is it the other way around? In “A Love Story”—one of the fiercest and funniest in the bunch—a pot dealer turned aspiring writer vents her frustrations with married sex life (or lack thereof), complains about raising children in the age of helicopter parenting (her critiques are witty and spot-on), and runs through the lives of women she’s encountered—her “own private Greek chorus”—in the dark before bed. She describes an uncle as being “so good at imagining things [that] he makes the imagined things real.” This excellent, inventive collection does the same; it is rife with observant asides, sly humor, and surprises.

What Goes Up

In Kennedy’s big-hearted second novel (after Learning to Swear in America), scientists have proven that the universe is infinite, NASA created the Interworlds Agency to explore the implications, and it’s looking to add a young new team to its roster. After a grueling two-day tryout, two standouts are chosen: Rosa Hayashi, privileged and brilliant, and Eddie Toivonen, who hitched his way to the trials and is running from an abusive father. When a strange spacecraft arrives, it quickly becomes evident that its occupants aren’t of this Earth nor are they here to make friends. Eddie, Rosa, and two other new recruits intervene, desperate to stop what could be the end of this world. Kennedy again shows a knack for portraying real teens dealing with extraordinary circumstances. While her heroes are as smart and talented as it gets, they’re still just kids looking for a bright future, a sense of belonging, and friends who have their back. Smart science, plenty of action, and no small amount of snarky banter round out an exciting and poignant read. Ages 13–up.

The Library of Fates

Princess Amrita of Shalingar, 16, lives a sheltered life within the palace walls. Her father, Chandradev, devastated by the death of his wife, has kept his only child far from the eyes of his people. But Amrita is forced to flee after Sikander, the emperor of Macedon and one of Chandradev’s former schoolmates, visits their home under the guise of solidifying a union between the two nations through marriage—and instead attacks her father and overthrows his regime. With an oracle named Thala as her guide and companion, Amrita endeavors to save her people from Sikander, as well as figure out who she truly is. Khorana (Mirror in the Sky) creates a beautiful and fantastical version of our world where gods and spirits walk among mortals. The fables repeated throughout foretell Amrita’s journey, seamlessly interweaving her past and future and mirroring a thought-provoking narrative that touches on weighty philosophical questions. This well-crafted novel leaves no questions unanswered, and although the path that Amrita eventually takes is unexpected, it’s very satisfying. Ages 12–up.

Like a Fading Shadow

Blurring fiction, memoir, and biography, the absorbing latest from Molina tells two stories: James Earl Ray’s 10-day excursion to Lisbon while on the run after assassinating Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, and the author’s own research trip to the same city in 1987 when writing his first novel, A Winter in Lisbon. Ray, living under an alias, travels using a Canadian passport and chooses Lisbon on a whim. Once there, he sleeps with prostitutes, drinks, and attempts to gain passage to Rhodesia, where he believes the colony’s white supremacist movement will embrace him. Nearly 20 years later, Molina, a new father, travels to Lisbon for the first time, looking for literary inspiration. As his travels to Portugal continue over the years, his marriage dissolves, he takes up with a new partner, and he becomes interested in Ray’s brief stay. The novel reconstructs the past with incredible detail, and Molina spins multiple possibilities for moments when Ray’s actions are uncertain. The result is a fascinating dual portrait of a writer looking into the clouded mind of a murderer.

Arbitrary Stupid Goal

Shopsin (Mumbai New York Scranton) weaves a marvelous patchwork quilt of stories about a Manhattan that doesn't exist anymore—that of 1970s Greenwich Village, where her father opened Shopsin's General Store. Her narrative reads like prose poetry with the rhythm of a jazz song: much of each page is left blank, as if to emphasize the words she doesn't use; the arrangement of her spare, blunt paragraphs conjures vivid pictures throughout ("Channeling photos of old New York with clotheslines strung from every building, I ran one on a hypotenuse from my fire escape to my farthest window"). Shopsin's narrative is decidedly nonlinear: she bounces among stories of her father's best friend Willoughby; working in her parents' store-cum-restaurant; taking trips with her partner, Jason; and the diverse characters from the neighborhood. Shopsin, who now cooks at the restaurant, doesn't shy away from her city's lows, such as the high crime rate at the time, explaining that her father's store got broken into nearly every week. The seemingly disparate tales come together into an artistic ode to a way of life that people now living in New York City might never experience.

Henry David Thoreau: A Life

In this definitive biography, the many facets of Thoreau are captured with grace and scholarly rigor by English professor Walls (The Passage to Cosmos). By convention, she observes, there were “two Thoreaus, both of them hermits, yet radically at odds with each other. One speaks for nature; the other for social justice.” Not so here. To reveal the author of Walden as one coherent person is Walls’s mission, which she fully achieves; as a result of her vigilant focus Thoreau holds the center—no mean achievement in a work through whose pages move the great figures and cataclysmic events of the period. Emerson, Hawthorne, and Whitman are here; so are Frederick Douglass and John Brown. Details of everyday life lend roundness to this portrait as we follow Thoreau’s progress as a writer and also as a reader. Walls attends to the breadth of Thoreau’s social and political involvements (notably his concern for Native Americans and Irish-Americans and his committed abolitionism) and the depth of his scientific pursuits. The wonder is that, given her book’s richness, Walls still leaves the reader eager to read Thoreau. Her scholarly blockbuster is an awesome achievement, a merger of comprehensiveness in content with pleasure in reading.