This week: a modern true crime classic, plus an incisive collection of essays about the issues facing black feminists.

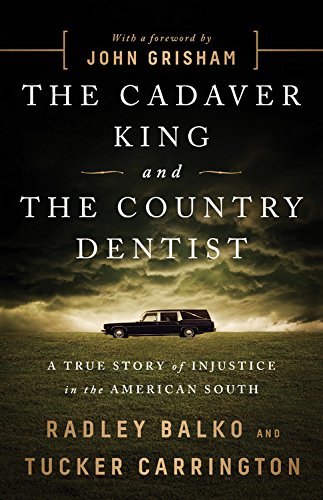

The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist: A True Story of Injustice in the American South

Investigative reporter Balko and former criminal defense lawyer Carrington offer a clear and shocking portrait of the structural failings of the U.S. criminal justice system in this account of two medical professionals—Steven Hayne, Mississippi’s “former de facto medical examiner,” and his friend Michael West, a forensic dentist—who, in turn, built successful careers off of a broken system. The book focuses on the doctors’ roles in the trials of Kennedy Brewer and Levon Brooks, who were both wrongly convicted of crimes involving the sexual assault and murder of minors in the 1990s (both men were exonerated in 2007). The authors methodically dissect the doctors’ testimonies in the trials of the two men and point to major flaws; such as when, during Brooks’s trial, Hayne asserted that marks on the corpse were definitely human bite marks, despite the condition of the body, which had been submerged in water and was badly decomposed. The authors make clear that these two false convictions resulted from the willingness of Mississippi authorities to overlook legitimate questions about the quality of Hayne’s and West’s work; for example, Hayne, who performed 80% of the state’s autopsies for more than two decades, once wrote that he had removed the uterus and ovaries from a male cadaver. This eminently readable book builds a hard-to-ignore case for comprehensive criminal justice reform.

A Girl Like That

Bhathena makes an impressive debut with this eye-opening novel about a free-spirited girl in present-day Saudi Arabia. Orphaned at a young age, Zarin Wadia moves in with her uncle and abusive aunt, who constantly shames and beats her. “Some people hide, some people fight to cover up their shame,” Zarin explains. “I was always the kind of person who fought.” Her treatment at school is even worse—she’s shunned for being different (she’s Zoroastrian, for starters) and responds by smoking cigarettes and sneaking out with boys. After Zarin gets reacquainted with a childhood friend, Porus, she becomes dependent on him for escape, protection, and the type of gentle affection she has not felt since her mother’s death. Readers know from the outset that Zarin and Porus die in a gruesome car accident, and their reflective post-death narratives share space with chapters written from the perspectives of others in their orbits. Bhathena’s novel should spur heated discussions about sexist double standards and the ways societies restrict, control, and punish women and girls. Ages 14–up.

A Good Day for Seppuku

This extraordinary collection from Braverman (Lithium for Medea) features unforgettable stories of women on the edge, children overlooked, and men at the ends of their ropes. In “What the Lilies Know,” a sober academic is denied tenure and travels to reunite with her estranged hippie mother, throwing the life she has built to the wind: “She left AA at the border. And half her IQ.” In “Cocktail Hour,” the wife of a wealthy doctor explains matter-of-factly that she is leaving him, effectively retiring from their marriage after raising their children—but he might have one last, gut-wrenching way to make her stay. In “Skinny Broads with Wigs,” a seemingly “neutered and eccentric” high-school English teacher spends her school vacations searching Los Angeles for her prostitute daughter. And, in the brilliant “Women of the Ports,” two childhood friends indulge in their yearly reunion, getting drunk and bluntly, unsentimentally recalling the various cruelties of their pasts. Braverman writes forthright but beautiful sentences. Her details are so vivid that they feel like memories: water is “last ditch leukemia IV-drip blue”; a lonely young boy is “sympathetic to the moon, barren, pock-marked and futile.” Without glorifying or reveling in suffering, Braverman reveals the inner lives of her disparate cast of characters.

Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower

Cooper, Cosmopolitan contributor and cofounder of the Crunk Feminist Collective blog, provides incisive commentary in this collection of essays about the issues facing black feminists in what she sees as an increasingly retrograde society. Many of the essays are deeply personal, with Cooper using her own experiences as springboards to larger concerns. In the essay “The Smartest Man I Never Knew,” Cooper uses the story of the attempted murder of Cooper’s mother (while she was pregnant with Cooper) by her mother’s jealous boyfriend as an example of American culture’s toxic masculinity. Elsewhere in the collection, the author explores her own identity as a black, Southern, Christian feminist and the ways in which personal politics can become incongruous, and she openly admits her own privilege. Cooper is at her best and most inflammatory in an essay titled “White Girl Tears,” in which she bulldozes white feminists for cultural appropriation and failing to “come get their people” during the 2016 presidential election. Cooper also cleverly uses Michelle Obama’s hair to craft an artful censure of respectability politics and discusses Beyoncé as a cultural symbol of black female solidarity. In these provocative essays, Cooper is both candid and vulnerable, and unwilling to suffer fools.

Behemoth: A History of the Factory and the Making of the Modern World

Freeman (American Empire), professor of history at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center, recounts the development of the factory, which over the past 300 years has come to symbolize both utopian possibilities and appalling realities. He notes that “we live in a factory-made world,” yet most consumers know little about these places or the experiences of those who work in them. Freeman begins in 18th-century England with the first factories, which were synonymous with filth and misery—William Blake’s “dark satanic mills.” He moves to 19th-century New England, where paternal industrialists hoped that they could both reap large profits and provide their employees with excellent working conditions; their idealism was soon replaced by a drive for ever-greater profits. Freeman is sharply critical of the technocrats and managers who regularly attempt to reduce wages and increase control over labor, yet he also sees the factory as a workplace that holds the possibility of liberation; Ford auto workers’ successful unionizing efforts, for example, “gave mass production a new, more democratic meaning.” Freeman goes on to describe modern Chinese factories, noting that some have become notorious for conditions that have caused workers to commit suicide, while others offer lavish recreational amenities that are irresistible to rural migrants. This wide-ranging book offers readers an excellent foundation for understanding how their possessions are made, as well as how the factory system affects society.

Fatal Discord: Erasmus, Luther, and the Fight for the Western Mind

Massing (Now They Tell Us), a former executive editor for the Columbia Journalism Review, superbly accomplishes the mammoth task of writing a dual biography of Desiderus Erasmus (1466–1536) and Martin Luther (1483–1546) that places the pair within their historical context. Massing argues that the schools of thought represented by Erasmus and Luther—a pluralistic humanism and an evangelical religion, respectively—still shape Western religious and political thought today. Erasmus, a Catholic priest, lived in the Netherlands; his translation of the New Testament sparked a large debate around authorship and intent. Luther, a German monk, famously launched the Protestant Reformation. Massing writes an entertaining, briskly paced narrative that whisks readers among the Low Countries, Paris, Germany, and England to ground the story within the complex theological history that helped to shape the work and lives of Luther and Erasmus. Apart from a few small stumbles—Massing seems not to understand the significance of the “golden rose” sent to England’s King Henry VIII by the pope, for example, although he later correctly explains the same symbol sent to Elector Frederick—this is a masterly work. Massing manages to juggle the complicated biographies and life work of both Erasmus and Luther while giving the reader a well-written, comprehensive background of pre-Reformation theology.

I’ll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman’s Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer

This posthumous debut recounts the chilling crimes of a serial murderer in California in the 1970s and ’80s, alongside the indefatigable investigation of crime writer McNamara to uncover the identity of the killer decades later. When McNamara first started writing about the case on her website TrueCrimeDiary in 2011, DNA testing had already linked 10 murders and 50 sexual assaults to one unknown man. The culprit, whom McNamara later gave the moniker “The Golden State Killer,” was a serial rapist in San Francisco’s East Bay in the mid-1970s, attacking women and girls in their homes. But in 1979, a close encounter with law enforcement led to a change in his M.O., and from that point on no one survived his attacks. McNamara fills in each crime with haunting details (“The suspect began clicking scissors next to blindfolded victims’ ears”) and tells the story of her own investigation, going as far as to track down and purchase from a vintage store a pair of cuff links that she believed the Golden State Killer stole from a victim. By the time of her sudden death in 2016, McNamara had inspired an online community of sleuths who continue to research the crimes. With its exemplary mix of memoir and reportage, this remarkable book is a modern true crime classic.

Silver Girl

The latest from Pietrzyk (Pears on a Willow Tree) is a profound, mesmerizing, and disturbing novel that delves into the vagaries of college relationships and how the social-financial stratum one is born into reverberates through one’s life. The unnamed narrator—hailing from a poor family headed by an abusive father in Iowa—is befriended by her roommate, Jess, a charismatic Chicago socialite, during their freshman year at an unnamed university in Evanston, Ill. She wants to hide her past and reinvent herself. Meanwhile, Jess’s father sends his mistress’s daughter to live with the two girls after she accidentally poisons her mother. This strains the alliance between the two young women, already tenuous because of underlying jealousies and competitiveness. The narrator makes the same mistakes over and over again in her personal life, and the author posits that there is a way out, but at a cost. In addition to capturing college life on a Midwest campus, Pietrzyk brilliantly depicts the push-and-pull dynamics between the two women, resulting in a memorable character study.

How He Loved Them

Prufer (Churches) considers the complex relationship between beauty and violence in his remarkable seventh collection of poetry, tracing the barely perceptible ways that industrial modernity “gilds us until we glitter.” The volume, consisting largely of individual lyric pieces, is gracefully unified by the poet’s willingness to inhabit the interstitial space between wonder and fear. “The moon is a hole/ in somebody’s skull,” Prufer writes, presenting readers with imagery as ominous as it is alluring, and in language that’s simultaneously stark and lyrical. As the collection unfolds, Prufer’s performative style reads as a deft commentary on the ethical concerns around which the poems orbit, largely the dangers and possibilities of finding beauty in a degraded world. Startling line breaks often appear as “a crack/ against the bright glass,/ a burst of black/ feathers.” Similarly, many of the book’s extended sequences get interrupted mid-thought by well-timed breaks. This subtle presence of such silences across the collection cultivates a provocative and fitting sense of unease on the part of the reader, who is apt to marvel at the language, unsure if harm will come to the imaginative world that is being constructed. In such a way, Prufer subtly implicates the audience in this accomplished, highly nuanced inquiry into spectacle and spectatorship.

Baby Monkey, Private Eye

A nearly 200-page chapter book for emerging readers? Using a pared-down vocabulary and luxuriant, chiaroscuro drawings, Selznick (The Marvels) and husband Serlin make it work—brilliantly. Four oddball robbery victims show up at Baby Monkey’s Sam Spade–worthy office, including a chef whose pizza has gone missing and a clown who has had his red nose stolen. Baby Monkey’s basic MO is always the same: look for clues, take notes, eat a snack, put on pants, and solve the crime (generally by looking right outside his office door). The tight, repeating structure gives Selznick plenty of opportunity to riff on the details: in each chapter, Baby Monkey has a different (and triumphant) wrestling match with his pants, and the furnishings of his office change to match the profession of each client (for those who can’t guess these Easter eggs, a key and index are included). “Hooray for Baby Monkey!” are the last words of this endearingly funny graphic novel/picture book/early reader—it’s a sentiment that readers of all ages will wholeheartedly affirm. Ages 4–8.

The Möbius Strip Club of Grief

Balancing a confessional voice with humor and portentous imagery, Stone (Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours) explores grief, familial connection, and the small things that sustain life in her startling third collection. Readers encounter feuds with Anne Sexton’s nieces and a hereafter where the dead perform for the living. But Stone’s great achievements are two sequences that share an awed admiration for the female mind. The first, “I am Unfaithful to You with My Genius,” is an ode to women writers and their “demon of genius—mad genius,” inspiring the poet to devotion: “like Antigone I would ruin myself for you.” The second, “Blue Jays,” pays homage to the poet’s mother, and by extension all women (“Mothers are all I have ever known”). Stone captures her mother’s eccentricities and burdens with heartbreaking clarity: “your genius trapped like a moth on the screened-in porch of your pain.” The book ends in a somber elegy for America—“I feel the phantom limbs of my predecessors/ waving in the air,” Stone writes—putting an exclamation point on a collection that features a bravely vulnerable beating heart hidden beneath layers of irony and clever misdirection. Stone is the child of her muses, Sexton and Emily Dickinson, and it is an odd but delightful union.

We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights

Journalist and law professor Winkler (Gunfight) evenhandedly traces key interactions between the Supreme Court and U.S. corporations to demonstrate how the controversial Citizens United decision was merely “the most recent manifestation of a long, and long overlooked, corporate rights movement.” Winkler starts his history in colonial America, showing how corporations such as the Virginia Company and Massachusetts Bay Company shaped American life from the very start. The rest of the book focuses on pivotal Supreme Court decisions, from 1809’s Bank of the United States v. Deveaux, over the corporate right to sue, through 2014’s Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., over religious rights. Winkler’s research is impressively thorough and wide-ranging, including original court records and news coverage as well as other historians’ analyses and interpretations. His argument is well supported throughout. Historical personages, from the well-known (Andrew Jackson, Henry Ford) to the more obscure (Roscoe Conkling, Charles Evan Hughes) to the downright surprising (Cecil B. DeMille), make appearances. He somewhat overstuffs the book with facts and backstory, some of which are only tangential to his project, but all are worthy of attention. Winkler employs an evocative, fast-paced storytelling style, making for an entertaining and enlightening book that will likely complicate the views of partisans on both sides of the issue.

Eat the Apple: A Memoir

In this bold memoir, ex-Marine Young examines how war transformed him from a confused teenager into a dangerous and damaged man. Fresh from high school and with no direction, Young walked into a Marine recruitment center in 2005 and sealed his fate. Soon he was suffering the indignities of basic training before being deployed to “the sandbox” in Iraq, where he sweated, masturbated, shot stray dogs, and watched friends get blown up. Despite the constant misery and suffocating discipline, Young redeployed twice more and even volunteered for Iraq on his last tour. Brief stints in the U.S. that blurred away into drunken violence and infidelity made war seem far safer to Young than civilian life. Eschewing first-person memoir conventions, Young, now a creative-writing professor at Centralia College, presents his experiences through a broad range of narrative approaches—second person, third person, first-person plural, screenplay, crude drawings, invented dialogue between various selves, etc. There’s real risk of trivializing the material, but Young matches his stylistic daring with raw honesty, humor, and pathos. Comparisons to Michael Herr’s Dispatches, about the Vietnam War, are apt, but where Herr searched for thrills and headlines as a journalist, Young writes from a grunt’s perspective that has changed little since Roman legionnaires yawned through night watch on Hadrian’s Wall: endless tedium interrupted by moments of terror and hilarity, all under a strict regime of blind obedience and foolish machismo.