This week: Michael Chabon on fatherhood, plus Michael Pollan on how to change your mind.

The Gone Away Place

Barzak (Wonders of the Invisible World) shows his expertise in conjuring a palpable sense of otherworldliness in this sad and eerie tale set in Ohio. Following a fight with her boyfriend, Noah, high school senior Ellie Frame decides to skip school to go to the lighthouse, a town landmark and popular refuge for teens. Here, she witnesses a succession of tornadoes that flatten much of the town and kill 150 people, including her three best friends and Noah. Reeling from grief, Ellie begins to see something over the next few weeks—the ghosts of people she knew, all of whom speak to her as though they were alive. Others in town have seen ghosts, too, and Ellie broods over why Noah, the person she misses most, has failed to make an appearance. The gray aura of tragedy might be oppressive if not for the book’s suspenseful elements and glimmers of light, small miracles that inspire hope and emotional healing. Ellie’s quest to find Noah and help other ghosts who want to be released from their bonds to earth is highly spiritual and deeply moving. Ages 14–up.

Be Prepared

Unlike her debut, Anya's Ghost, Eisner-winner Brosgol's second graphic work is a summer camp memoir set in the real world. Without fantasy elements to distract, execution is crucial, and Brosgol delivers. Vera, Brosgol's nine-year-old self, is a wide-eyed Russian immigrant kid desperate to fit in with her suburban classmates. They all go to camp every summer, and when she finds out about a Russian Orthodox camp that her family's church will help pay for, she talks her mother into letting her go. It doesn't take her long to realize that she's wished for the wrong thing. Mean girls, stinking outhouses, and baffling camp traditions make her first weeks miserable. Triumphs come, but not before she undergoes moments of humiliation that are both funny and cringeworthy ("Is that candy?" Vera asks her older tentmates about a pack of maxi-pads). The dialogue rings true, the pace is seamless, and the panel artwork, in woodsy browns and greens, conveys feelings with clean, assured lines. By turns sardonic, adorable, and noble, Vera is a beguiling hero who learns how to recognize who's really on her side. Ages 10–14.

I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness

In this powerful book, Brown is up front about her exhaustion with white people as she meticulously details the experience of being a black woman in modern American society. After explaining that her parents named her Austin so that potential employers would “assume you are a white man,” she recreates a typical interview and first few months at a new job: “Every pair of eyes looks at me in surprise.... Should they have known? Am I now more impressive or less impressive?... It would be comical if it wasn’t so damn disappointing.” In clear prose, she relates anecdotes to shed light on racial injustices that are systematically reinforced by the standards of white society. Brown, a Christian, believes the history of American Christianity is deeply intertwined with race relations and that Christian communities need to play a large role in racial reconciliation. Explaining that change needs to come from acknowledgement of systemic inequalities, Brown calls on readers to live their professed ideals rather than simply state them. Though the writing style can be preachy, Brown’s authoritative tone and moving message make this a must-read for those interested in racial justice within the Christian community.

Pops: Fatherhood in Pieces

Pulitzer-winning novelist Chabon (Moonglow) brings together a deeply affecting collection of essays that scrutinize and celebrate the complexities of relationships between fathers and their children. Selections range from the quietly heartbreaking, as when Chabon describes the inadvertent hurt a father can impart on a child, to the hilarious, as he describes his son taking his idiosyncratic sense of style into the “heteronormative jaws of seventh grade.” Avoiding an overly sentimental tone or rose-colored perspective, Chabon doesn’t shy away from reflecting on parental failures as well as successes. In the particularly moving essay “Little Man,” he regrets missing the signs one son sends as he struggles to create his own identity (“You are born into a family and those are your people, and they know you and they love you, and if you are lucky, they even on occasion manage to understand you. And that ought to be enough. But it is never enough”). Chabon is a gifted essayist whose narratives lead to unexpected and resonant conclusions. His work here packs an outsized emotional punch that will stick with readers significantly longer than it takes them to read this slim volume.

The Ensemble

Gabel’s wonderful debut centers on the talented members of the Van Ness String Quartet over the course of the 18 event-filled years following 1994. There’s Jana, violin 1, the natural leader; Henry, viola, the prodigy; Daniel, cello, the charming one who brings intensity to the group; and Brit, violin 2, the unknown quantity. They’ve slept with one another (Jana and Henry, Daniel and Brit) and are battered and bruised by the competition circuit. But, over the years, they stay together in the face of professional temptations (Henry is encouraged to make a solo recital debut), dueling egos (Jana incurs Henry’s jealousy when she sleeps with another violinist), rivalries (Daniel is intimidated by the members of a younger quartet), injuries, and bad judgment. Along the way, they also manage to become husbands, wives, and parents. But despite all these distractions, the love of making music is what keeps Jana and the others imperfectly bound to one another. Seldom has a novel managed to better dramatize the particular pressures that make up the life of a professional musician, from the physical pain of contorting limbs over a long period of time to the emotional stress of constantly making adjustments to the changing temperaments of partners. Readers will come away with a renewed appreciation for things people usually take for granted when listening to music. The four characters are individually memorable, but as a quartet they’re unforgettable.

When Einstein Walked with Gödel: Excursions to the Edge of Thought

Inspired by the unlikely friendship of gregarious physicist Albert Einstein (1879–1955) and gloomy logician Kurt Gödel (1906–1978), who met at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study in 1943, Holt (Why Does the World Exist?) fills his fantastic essay collection with stories about eccentric geniuses and groundbreaking ideas at the intersection of science and philosophy. Two criteria link the essays: the first is “the depth, power, and sheer beauty of the ideas they convey,” and the second is what Holt calls the “human factor”—specifically that the ideas originated in the minds of people who led highly dramatic or even absurd lives. Einstein’s theory of relativity upended everyday notions about the world, in the same way that Gödel’s incompleteness theorems subverted notions about the abstract world of mathematics, and both men certainly lived dramatic lives—particularly Gödel, who starved himself to death under the delusional suspicion that everyone was trying to poison him. The men’s friendship provides a framework that leads readers to Victorian school teacher Edwin Abbott, whose satirical novella Flatland presages a look at other dimensions; computing pioneers Ada Lovelace and Alan Turing; fractal discoverer Benoit Mandelbrot; and Francis Galton, the creator of modern statistics, among others. Holt delivers this feast of wild genius, oddball thinkers, and sheer creativity in his signature accessible style of writing and playful tone.

The Favorite Sister

Knoll (Luckiest Girl Alive) explores the blurry line between a reality show and real life—and the duplicity of family ties and friendship—in this razor-sharp, darkly comic thriller. The grisly murder of spin and yoga studio entrepreneur Brett is revealed at the outset of this briskly paced whodunit; the narrative then flashes back, unfolding the complex how and why from the perspectives of narrators Brett, the overweight “least-loved sibling”; her thin and pretty sister Kelly, who abandoned a high-profile career path to be a single mom and run Brett’s growing business empire; and bestselling author Stephanie. All three are contestants on the reality show Goal Diggers, which hypes the accomplishments of “unmothers and unwives” and is run by conniving and high-profile network executive Jesse. The characters compete for prominence, audience popularity, and social media buzz. It’s off-screen where things take a dark turn: Brett’s “enigmatic gay millennial” persona comes apart and Stephanie’s bestselling memoir is exposed as anything but true. Though the mystery is engrossing enough in its own right, Knoll’s novel is most notable as a potent takedown of a reality-show-obsessed culture that seeks out the spotlight rather than harder truths.

How It Happened

With this searing look at an investigator’s obsessive efforts to close a case that has reawakened childhood demons, bestseller Koryta (Rise the Dark) has produced his most powerful novel in years. FBI agent Rob Barrett feels he has “a firm sense of the truth and no evidence to back it up” after he extracts an unsubstantiated confession from 22-year-old Kimberly Crepeaux, who admits to a role in killing Jackie Pelletier, the daughter of a prominent fisherman in Port Hope, Maine, and Jackie’s boyfriend, Ian Kelly. In fact, Kimberly, who has a reputation for being a liar, provided incorrect details about where their bodies could be found. Still, Barrett, an inexperienced agent with a reputation as a superior interrogator, credits Kimberly’s account. According to her, her co-conspirator, 29-year-old Mathias Burke, a “local source of pride” who has a successful landscaping and remodeling business, first ran Jackie down with his truck and then bashed Ian’s head in before dumping their corpses in a pond. As Barrett, who knew Burke growing up in Port Hope, tries to ferret out the truth, certain aspects of the case revive painful memories of his mother’s inexplicable death when he was eight. Koryta, when he’s at the top of his game, has few peers in combining murder mysteries with psychological puzzles.

All the Answers: A Graphic Memoir

An artist races to uncover and understand his father’s unusual childhood before his memories are lost to the onset of dementia in this striking and tragic memoir. Self-presenting as a neurotic mess, Eisner Award–winning Kupperman (Tales Designed to Thrizzle) dives into the (for him) unknown story of how his father Joel, a math whiz turned philosophy professor and author, had once been “manufactured” as the marquee child star of the hit World War II–era radio show Quiz Kids. The show made Joel a star, but it was also a traumatic experience that turned him into an emotionally distant man and an uncommunicative parent. The narrative pivots between Kupperman’s reconstruction of stranger-than-fiction moments unearthed from his father’s repressed memory—including the time Joel, a Jewish child on a show developed in part to combat anti-Semitism, met with rabid anti-Semite Henry Ford—and his present-day attempts to get the story straight in the shadow of Joel’s encroaching illness. Kupperman’s varied angles, thick line work, staring seriocomic facial stylings, and sharp prose help turn an already incredible story into an electrifyingly fast-paced, yet intimate memoir about family secrets and the price children can pay for their parents’ ambitions.

The Lives of the Surrealists

Morris (The Naked Ape), the last surviving member of the first-generation Surrealists, offers an intimate tour of the personal lives of the artists in his inner circle. The motley assortment ranges from textbook staples (Salvador Dalí) to those on the movement’s margins (Alexander Calder). Morris’s emphatic focus is not on their art but their lives. Writing as a personal friend and acquaintance of many of the Surrealists, he divulges their working habits (Alberto Giacometti was a night owl who regularly went to bed at 7 a.m.), personality quirks (Leonor Fini spent hours studying corpses), and sexual conquests with a disarming familiarity (each entry begins with a list of sexual partners). The movement’s founder and fulcrum, Andre Breton, is cast as something of an unlikable, controlling bully who at one point or another expelled nearly all of the Surrealists from the movement, occasionally with unintentionally humorous theatricality. Morris concedes, however, that the movement “would have been much the poorer without him.” Each of these 32 short biographical entries is thoughtfully accompanied by a lesser-known work of art by each artist, along with photographs of the artists as they appeared in their most active years. Alternatively funny, ribald, and at times genuinely moving, Morris’s fittingly off-kilter tribute to the Surrealist movement itself and the eclectic men and women who carried its torch is a true joy.

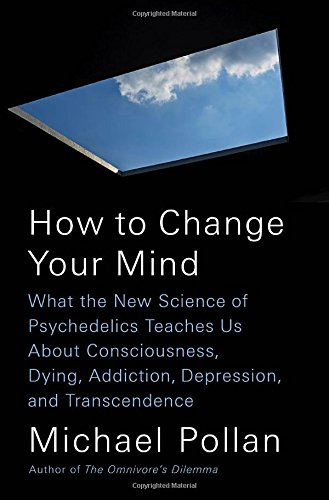

How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us about Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence

Food writer Pollan (Cooked) shifts his focus to other uses of plants in this brilliant history of psychedelics across cultures and generations, the neuroscience of its effects, the revival of research on its potential to heal mental illness—and his own mind-changing trips. For an entire generation, psychedelics were synonymous with Harvard professor-turned-hippie Timothy Leary and his siren call to “turn on, tune in, drop out.” But, Pollan argues, that freewheeling attitude quickly turned into a “full-on moral panic about LSD” that “doomed the first wave of [psychedelic] research.” By the 1990s, the body of knowledge about the successful use of LSD to treat alcoholics in the ’50s and ’60s was buried, and medical interest only revived in 2010 with studies on treating cancer anxiety with psilocybin. Pollan writes movingly of one man whose “psychedelic journey had shifted his perspective from a narrow lens trained on the prospect of dying to a renewed focus on how best to live the time left to him.” Today, renewed interest has sent scientists racing ahead with trials of psychedelics to treat addiction and depression, and curious seekers like Pollan into experiments with these substances. This nuanced and sophisticated exploration, which asks big questions about meaning-making and spiritual experience, is thought-provoking and eminently readable.

Last Stories

This spare collection of 10 stories by the late Trevor (The Story of Lucy Gault) might be too bleak if its darkness weren’t skillfully counterbalanced by sly hints of humor and understated compassion. The stories are sharp and concise, containing whole lives in the span of just a few pages. The book as a whole has an elegiac tone, with death figuring heavily in many of the stories. Often, it’s death observed at a distance, as in “The Crippled Man,” in which two foreign painters speculate about the disappearance of one of the owners of the house they are painting, or “The Unknown Girl,” in which the former employer of a young woman killed crossing the street wonders whether she holds partial responsibility. Many of Trevor’s stories contemplate two interacting characters who have little in common, like the prostitute who pursues a picture-restorer whose memory is failing in “Giotto’s Angels,” or the very different widow and widower in “Mrs Crasthorpe.” The author keeps a distance from his characters, driven to incomprehensible actions by motives even they don’t understand. Readers familiar with Trevor, who died in 2016, will find satisfying closure, and those new to his work will find reason to go back and explore his previous books.