This week: how the U.S. blew the whistle on the world’s biggest sports scandal, plus the lost world between England and Scotland.

The Button War: A Tale of the Great War

Darker than the Newbery Medalist’s usual fare, this powerfully evocative WWI novel set in Poland parallels a child’s game with the war raging in the not-so-distant background. After the Germans bomb the schoolhouse and the long-residing Russian soldiers prepare to leave the area, Patryk’s small, isolated village is suddenly a whirlwind of activity. Inspired by the frequent comings and goings of military men, Jurek, the cruel, conniving leader of Patryk’s group of classmates, declares a daring challenge: whoever procures the best button from a soldier’s uniform gets to be king. Patryk is determined to beat Jurek at his own game, but he is no match for Jurek’s determination to win at all costs, even as the game turns deadly. Told from Patryk’s point of view, the novel captures the ways that war can forever alter a child’s sense of order, morality, and security in the world. Strongly visual scenes, including the smoky forest after battle, the soldiers marching in perfect formation, and a chilling final image of Jurek, will long resonate in readers’ minds. Ages 10–14.

And Then We Danced: A Voyage into the Groove

In his exhilarating book, Thurber Prize–winner Alford (Big Kiss) examines the various functions of dance in American culture through a combination of hilarious, self-deprecating narration and detailed reporting. Alford weaves in the biographies of seminal dancers and choreographers throughout, such as Savion Glover’s use of nostalgia in his work and Twyla Tharp’s repeated acts of rebellion against the dance canon, but he’s at his best describing how these functions have influenced his own life and those of everyday people (dance is a “fully immersive experience that allows us to meld with other people”). As a participatory journalist, Alford delves deep into the world of contact improv, and experiences the genre’s profound levels of intimacy; recounts his own use of dance to release pain and emotion (when he was upset, he brought his pain to dance classes and “thrashed it out”); and witnesses firsthand dance’s rehabilitative powers for seniors with dementia and Alzheimer’s. Packed with countless laugh-out-loud anecdotes (“If you get it right, the effect is that of a stork with a trick knee trying to take flight”) and insightful examinations of human interaction and culture, Alford’s latest will charm and intrigue dance enthusiasts of all kinds.

Red Card: How the U.S. Blew the Whistle on the World’s Biggest Sports Scandal

In his intense first book, investigative journalist Bensinger explores the U.S. Department of Justice’s investigation into corruption at the highest levels of international soccer. The story begins with a 2011 Google alert received by Steve Berryman, an Internal Revenue Service special agent and zealous soccer fan, about high-ranking FIFA official Chuck Blazer—an American whose financial records were under examination by the FBI. With that tip, Berryman teamed with FBI agents to go after Blazer, who, facing significant federal charges, eventually became the government’s most helpful cooperator in the investigation. Bensinger colorfully details the global pursuit of Blazer’s cronies that climaxed in May 2015, when several FIFA officials were arrested for allegedly accepting hundreds of millions of dollars in bribes to influence the selection of host countries for the World Cup. Among those arrested were Jack Warner, a cocky yet quiet Trinidadian who was president of the Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football, and his successor, Jeffrey Webb, a Caymanian with five homes in the U.S. and aspirations of becoming president of FIFA. A total of 18 people were indicted, and the fallout from the scandal included the resignation of FIFA’s longtime president, Sepp Blatter. With the flair of a novelist, Bensinger meticulously chronicles the magnitude of corruption that permeates the world’s most popular sport.

Before and After Alexander: The Legend and Legacy of Alexander the Great

Columbia University history professor Billows (Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western Civilization) provides a thorough analysis of the legacy of history’s most famous conqueror. According to Billows, Alexander the Great was more of an accident of history than a maker of it, and so he focuses on the transformative eras before and after Alexander’s 13-year reign—Alexander first appears at the book’s halfway point and is gone after a single chapter. Billows argues that Alexander was only able to conquer the lands between Greece and India on the strength of Macedonia’s established military might. It was under the 24-year rule of Alexander’s father, Philip II, that Macedonia became an economic and military power among the Greek city-states; in particular, he introduced and perfected the Macedonian phalanx military formation, which was used to its greatest effect in the wars of Alexander. After a period of civil wars, Alexander’s successors established the Antigonid, Seleucid, and Ptolemaic empires, all of which endured into the Middle Ages and spread Hellenistic culture, the Greek language, and libraries across Europe and Asia. The author meticulously defends his provocative thesis about Alexander’s role with in-depth historical analysis and an array of citations and quotes from primary sources, making this a clear, enlightening exploration of one of the most influential periods of human history.

Starless

This rich, evocative fantasy epic from Carey (Miranda and Caliban) is a poignant tale of grand adventure. Khai was chosen at birth to serve as shadow (a soul-twin and protector) for the Sun-Blessed Princess Zariya of the House of the Ageless. He has spent the entirety of his young life in the desert, preparing for this task the gods have bestowed upon him. As puberty draws near, Khai is due to be presented to the princess, but his position is undermined when he learns that he is bhazim, a daughter who was pledged to be raised as a son. He also learns of a prophecy that speaks of the fallen god, Miasmus, a darkness that will “arise in the west against which one of the Sun-Blessed will stand.” Pragmatic Zariya, who was injured in childhood and walks with canes, is determined to be that prophesied one with the aid of her shadow. Khai, cautiously experimenting with gender presentation, joins Zariya and the defenders of the four quarters, a ragtag group who are committed to halting Miasmus’s destructive force. Carey handles themes of duty, love, and identity with tenderness and fortitude, never pigeonholing her protagonists, and the tapestry of her characters elevates this novel above its peers.

The Verdun Affair

Dybek’s gripping second novel (after When Captain Flint Was Still a Good Man), a cleverly constructed page-turner, travels back and forth in time between a European continent devastated by World War I and 1950s Hollywood. Tom Combs is an American ambulance driver who stays on in the war’s aftermath to work for a priest, collecting the bones of dead soldiers from the battlefields of Verdun. He falls in love with Sarah Hagen, a fellow American, but she has come to France looking for news of her “missing, believed dead” husband. Sarah goes off in search of information, and Tom takes a job as a journalist in Paris. They meet again in Bologna in 1922, when a soldier creates a sensation after showing up in a hospital there with no recollection of who he is. Sarah believes the mysterious soldier is her husband, though others have reason to believe otherwise. Years later, Tom, working in Hollywood, comes across Paul, a fellow journalist from those heady days in Italy, and, reliving their unresolved past, they discover each entertains a different version of the truth. Dybek is a master at creating an atmosphere of war, of decadence amid the rubble, and at dipping in and out of history, teasing the reader with beguiling clues concerning the secrets each character harbors about the amnesiac. Dybek’s novel is a complex tale of memory, choice, and the sacrifices one sometimes makes by doing the right thing.

Splinter in the Blood

At the start of the enthralling debut from Dyer (the pen name for two British authorities on crime), Det. Sgt. Ruth Lake holds the gun that just shot her partner, Det. Chief Insp. Greg Carver, who’s been pursuing the Thorn Killer. Greg is slumped on the sitting room floor of his Liverpool house and, amazingly, alive. Before calling in the shooting, Ruth wipes all surfaces she touched and stashes in her car the box of evidence on the Thorn Killer, who has been terrorizing the city using poison-drenched thorns to kill his victims. When Greg wakes up in the hospital, he can’t remember anything that happened on the day he was shot, but he’s sure that his shooting is a warning not to get too close to the killer. While Greg recuperates in the hospital, Ruth, a former crime scene investigator, clandestinely pursues the Thorn Killer. But Ruth is harboring a dark secret that she’ll do almost anything to keep hidden. The skillfully constructed plot complements the intriguing characters, including a deliciously creepy killer who lurks in the background. Dyer is definitely a crime writer to watch.

The Color of Bee Larkham’s Murder

In this fantastic debut, Harris enters the technicolor mind of 13-year-old Jasper Wishart. Jasper has always had synesthesia, which for him means he sees specific colors for all the sounds around him—people’s distinct voices, barking dogs, slamming doors. Jasper, who lives alone with his disinterested father and suffers from learning disabilities, spends much of his time gazing out his window at an oak tree filled with parakeets. The parakeet-occupied tree across the street belongs to Bee Larkham, a new girl who has been causing trouble in the neighborhood by playing her music too loudly and feeding the noisy birds. Jasper’s synesthesia hampers his ability to recognize people’s faces, and when Bee suddenly disappears, Jasper, who keeps seeing the “ice blue crystals” of murder, must paint the events leading up to that night to get things straight and solve the mystery. Readers enamored of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time and The Rosie Project will delight in Harris’s sparkling novel.

Everything Else in the Universe

Holczer’s perceptive novel, set in 1971, opens as 12-year-old Lucy Rossi’s father returns home from Vietnam missing his right arm. Lucy and her parents have always been a mutually supportive team. Expecting this dynamic to continue, careful Lucy (who relies on her “behavioral comfort routines”) studies up on amputees and prosthetics, only to find her father resistant to her efforts. Bewildered by the change in her family, Lucy feels left out and unloved, particularly after she’s relegated to spending the days next door with her uncle’s boisterous family. A new friendship with Milo, who tells her his father is fighting in Vietnam, helps; his interest in dragonflies mirrors Lucy’s in rocks, and after they discover a soldier’s personal effects, they work together to find the owner. Affectingly tracing Lucy’s struggles with her altered family, Holczer also credibly portrays the conflicting views on the war, from protestors to former vets. Well-grounded in its era and peopled by fully realized characters, the book is a resonant historical novel and a thoughtful exploration of how war and injury affect family, friendships, and individual growth. Ages 10–up.

Bearskin

As taut as a crossbow and as sharp as an arrowhead, McLaughlin’s debut unfolds in the Appalachian wilderness of Virginia, a landscape whose heart of darkness pulses viscerally through its characters. Rice Moore is working as a biologist caretaker at the vast Turk Mountain Preserve when he discovers that poachers are killing bears to sell their organs on overseas drug markets. Rice’s efforts to curtail their activities antagonizes locals who raped the last caretaker and left her for dead, and—worse—it alerts agents of Mexico’s Sinaloa drug cartel, from which Rice has been fleeing for reasons revealed gradually, to his whereabouts. McLaughlin skillfully depicts Rice, revealing quirks and peculiarities of his personality that show how “his hold on what he’d always believed was right and what was wrong had grown fatigued, eventually warping to fit the contours of the world he inhabited”—a disconcerting revelation that helps establish the suspenseful feeling that anything can happen. Rice’s story builds toward violent confrontations with the poachers, the cartel, and nature itself. The novel’s denouement, a smoothly orchestrated confluence of the greater and lesser subplots, plays out against a tempest-tossed natural setting whose intrinsic beauty and roughness provide the perfect context for the story’s volatile events. This is a thrilling, thoroughly satisfying debut.

Convenience Store Woman

Murata’s slim and stunning Akutagawa Prize–winning novel follows 36-year-old Keiko Furukura, who has been working at the same convenience store for the last 18 years, outlasting eight managers and countless customers and coworkers. Keiko, who has a history of strange impulses—wanting to grill and eat a dead bird, pulling down a hysterical teacher’s pants to get her to be quiet—applied to work at the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart on a whim. Where someone else might find the expected behavior for convenience store workers arbitrary and strict, Keiko thrives under such clear direction, finally finding a way to be normal. In fact, she thinks of herself as two Keikos: her real self, who has existed since she was born, and “convenience-store-worker-me.” But normalcy is not static, as Keiko discovers. The older she gets, and the further she drifts from milestones like having a “real” job, marrying, and having children, the more her friends and family push her towards change. She strikes a sham marriage deal with a lazy and shifty ex-coworker, which, though it finally makes her “normal” in the eyes of others, throws her entire life and psyche into turmoil. Murata’s smart and sly novel, her English-language debut, is a critique of the expectations and restrictions placed on single women in their 30s. This is a moving, funny, and unsettling story about how to be a “functioning adult” in today’s world.

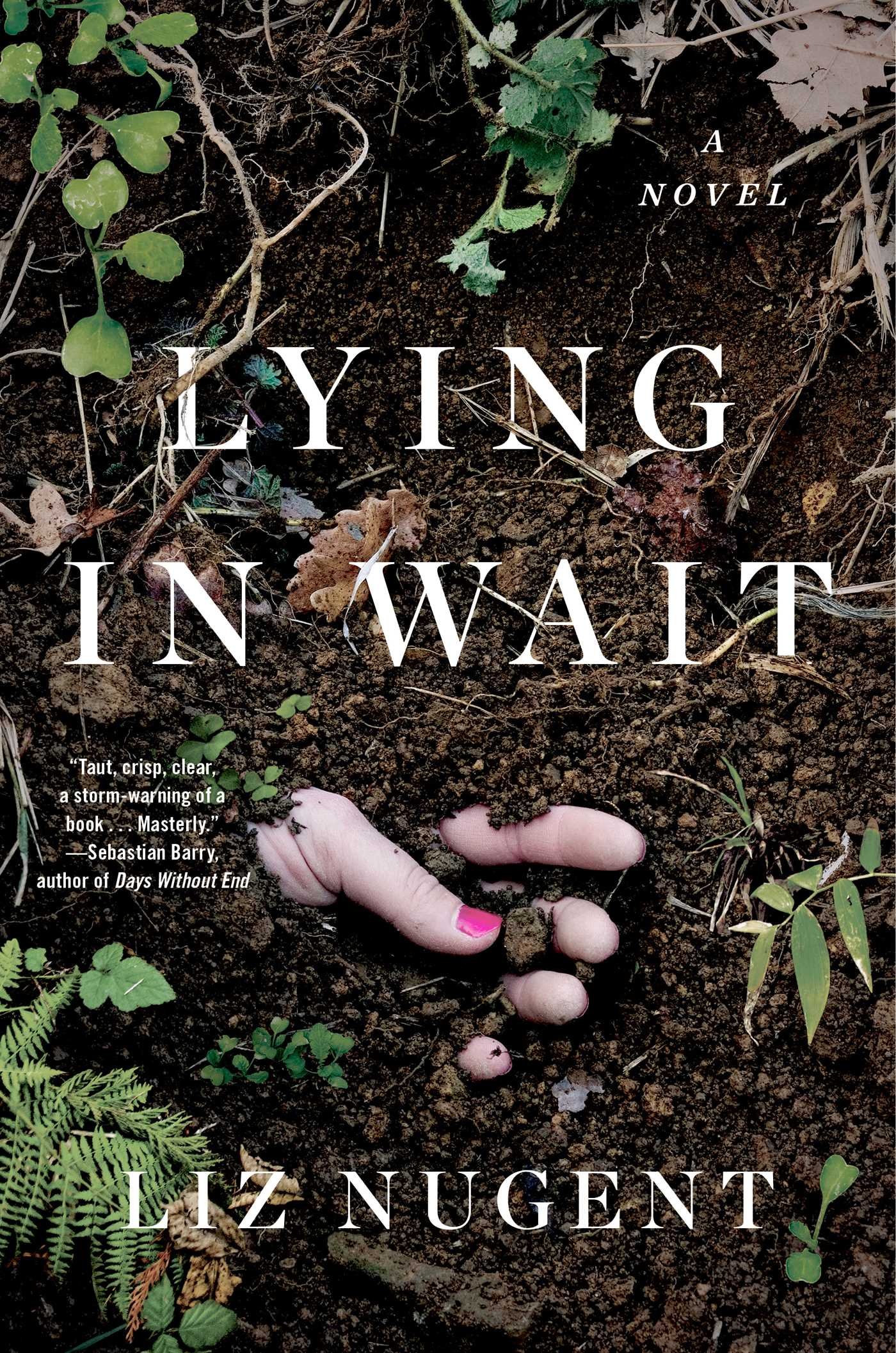

Lying in Wait

Irish author Nugent follows her well-received debut, 2017’s Unraveling Oliver, with a devastating psychological thriller. Late on the night of Nov. 14, 1980, judge Andrew Fitzsimons and his wife, Lydia, rendezvous with troubled 22-year-old prostitute Annie Doyle on a deserted Dublin beach for unspecified reasons. When Annie threatens blackmail, the couple kill her. Lydia orders Andrew to bury the body in their garden and forget it, but then Annie’s family reports her missing and a media circus ensues. Andrew panics, arousing the suspicion of the couple’s 17-year-old son, Laurence, who becomes obsessed with Annie. Also fixated is the victim’s 19-year-old sister, Karen, who remains dedicated to finding Annie even after the police lose interest. This tragic tale unfolds over five years from the perspectives of Lydia, Laurence, and Karen, allowing Nugent to develop character while exploring the crime’s ripple effect. Annie’s connection to the Fitzsimonses is the mystery on which the plot hangs, but Lydia is the most intriguing puzzle; equal parts victim and villain, she simultaneously inspires pity, outrage, and horror. The result is an exquisitely uncomfortable, utterly captivating reading experience.

The Debatable Land: The Lost World Between Scotland and England

Robb’s move to the singular “Debatable Land” on the border of present-day England and Scotland inspired this combination bicycle travelogue, regional history, and declaration of admiration. Covering 33,000 acres on either side of the Scottish-English border, this uninhabited middle ground originally, in ancient times, served as communal (“bateable”) livestock pastures, Robb (The Discovery of Middle Earth) explains, preserving a historically delicate balance in a region where family loyalty rules and accents vary significantly over a few miles. Later, a core group of families, like the Armstrongs and Nixons, made up the “reivers,” who made their living stealing livestock and household goods, leaving burned houses in their wake and introducing the words “blackmail” and “bereaved” into English. Robb’s passion for cycling and amiable persona provide him with a ground-level view, allowing him to observe how the reality of life in the borderlands differs from the myths, such as the inaccurate story that blames a curved ditch obstacle on “Anglo-Scottish strife.” Focusing on this one remarkable region, Robb’s two-wheeled perspective and highly observant eye allow him to ruminate through the Celtic, medieval, and present eras with ease; readers are lucky to join him on his enthralling journey.

Rising: Dispatches from the New American Shore

Timely and urgent, this report on how climate change is affecting American shorelines provides critical evidence of the devastating changes already faced by some coastal dwellers. Rush, who teaches creative nonfiction at Brown University, masterfully presents firsthand accounts of these changes, acknowledging her own privileged position in comparison to most of her interviewees and the heavy responsibility involved in relaying their experiences to an audience. These include the story of Alvin Turner, who has lived in his Pensacola home for more than five decades, survived numerous hurricanes, does not carry flood insurance, and lives “alone on the edge of a neighborhood threatened from all sides.” Alvin’s story is not unlike that of Chris Brunet, a native of the shrinking Isle de Jean Charles in a Louisiana bayou, who must decide whether to stay on the disappearing island or leave. While showing that today’s climate refugees are overwhelmingly those already marginalized, Rush smartly reminds readers that even the affluent will eventually be affected by rising sea levels, writing that water doesn’t distinguish “between a millionaire and the person who repairs the millionaire’s yacht.” Rush also presents a legible overview of scientific understandings of climate change and the options for combating it. In the midst of a highly politicized debate on climate change and how to deal with its far-reaching effects, this book deserves to be read by all.