Though we've named our Best Books of 2019, we all have our personal favorites, and not all of them are from 2019. These are the best books we read this year.

Anna and the Swallow Man by Gavriel Savit

With any book set during WWII, you have to gird yourself to a certain extent. It’s probably not going to be filled with sunshine and rainbows. I thought I was prepared when I started Anna and the Swallow Man, but I underestimated this short title. The tension that permeates this beautifully written story of a little girl and con man relying on each other to survive is masterfully done. I’m not going to lie. I cried quite a few times. –Drucilla Shultz, bookroom editor

Bel Canto by Ann Patchett

I often come late to books, and so I did last March in an airport bookstore to Ann Patchett’s 2001 hit, Bel Canto. It enthralled me for my seven-hour flight and turned out to be my favorite book of 2019. It's exquisitely written and masterfully paced, and Patchett springs a grim plot device a few pages in and from there, builds a reality that allows us to focus on characters we usually look past and emotions and dreams usually drowned out by day-to-day life. I am told the film adaptation with Julianne Moore was a turkey, but the book is as alive and valid today as almost 20 years ago–with no help needed from Hollywood. –Carl Pritzkat, V-P, general manager

Check, Please! by Ngozi Ukazu

I'd heard a lot about this webcomic turned graphic novel from friends but it wasn't at the top of my "To Read" list. When my sister began to insist I read it, I finally relented, with some hesitation since I wasn't the most knowledgeable person on hockey. It didn't even take me to the double digits for me to get hooked. The main character, Bittle, is both hilarious and endearing. Ukazu's research really shows and really helps a non-hockey fan such as myself learn about the game, but also doesn't set it up as your typical sports comic. It's very much about learning how to grow as a person coming from a small town to a big college. The main character is also a gay man who vlogs, loves to bake, and used to be a figure skater until joining a very rough and tumble sport in his first year of college. Now if I'm asked if I would I recommend this, I say abso-PUCK-ing-lutely! –Gilcy Aquino, intern

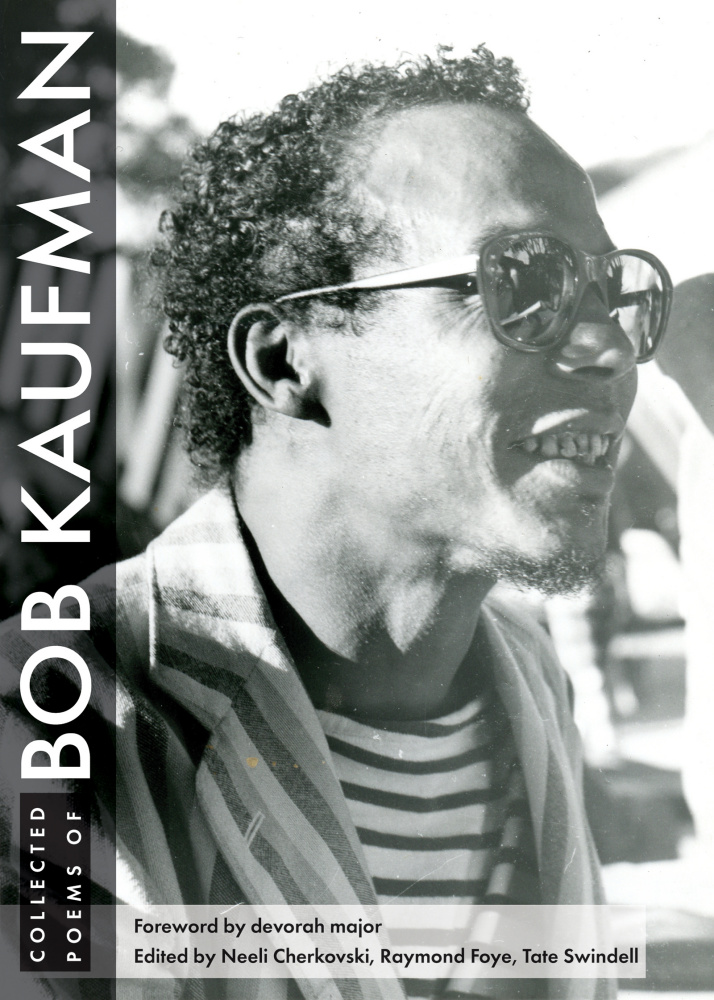

Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman edited by Neeli Cherkovski, Raymond Foye, and Tate Swindell

Among the great American mystic poets, few have made such enormous contributions while being so overlooked as Bob Kaufman. The Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman ends the African American surrealist’s exile from our poetic landscape, sharing the full breadth of his work for the first time. Closely associated with Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, and the San Francisco Beats, Kaufman’s enigmatic life has long been a focus for readers. But it is ultimately the simple fact of his poems, collected here in one volume, that matters most. In masterpieces like his 1965 “Abomunist Manifesto” and “Does the Secret Mind Whisper?” readers will encounter the rarest of writers; a poet who could shift from starkness and brutality to humor, tenderness, and wonderment in an instant. Not many collected works deserve sustained place in the hands of readers and on the shelves of bookstore poetry sections. This is one of them. –Alex Green, New England correspondent

Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture by Grace Elizabeth Hale

The history of American indie rock music is all about scenes—and in the 1970s and ’80s, wow, was there a scene in the sleepy college town of Athens, Georgia. For music geeks, historian Grace Elizabeth Hale’s treasure of a book gives Athens the love it deserves for giving the world some great bands (R.E.M., the B-52s, and the hugely underrated Pylon). But perhaps more importantly, Athens showed the world that you don’t need to be in New York, or LA, or London to make your cultural mark. Fair warning—this is a not an extended SPIN article—it’s a real work of history, written by an accomplished historian. The book is 300 tightly-packed pages, not including the endnotes, and is published by a venerable academic press (in fact, this will be the first title published under the University of North Carolina Press’s promising new endowed trade imprint, Ferris & Ferris Books). But let’s be honest—if you’re inclined to pick up a book on the indie scene in Athens in the first place, this is exactly what you want. And not a word of Hale’s deeply researched, yet also deeply personal narrative is wasted. As with many of the books I read (given my job here at PW) this book isn’t out until March—so, mark your calendar, and maybe give your local bookstore a heads up. And I recommend enjoying this book like I did—with a good bottle, and Spotify at the ready. –Andrew R. Albanese, senior writer

Go Ahead in the Rain by Hanif Abdurraqib

Exploring the background, formation, and rise of a group which formed amongst childhood friends in Queens, N.Y., Abdurraqib's erudite ode to A Tribe Called Quest walks readers through their unique formation, but also easily freewheels across late 80s and 90s pop and hip hop culture. It was a time of easy borrowing and lending. His depiction of a singular time in America (which he grounds in his own reflections of high school), when technology was changing everything rapidly and music felt less stratified, and his exploration of sample culture before the tightening effects of copyright laws, are particularly precise and just right. –Seth Satterlee, reviews editor

Hungry: Eating, Road-Tripping, and Risking It All with the Greatest Chef in the World by Jeff Gordinier

It's a food book that's not all about food. A travel narrative that's not really about travel. So what is it? It's kind of amazing, actually. Gordinier spent a good chunk of several years traveling the globe with René Redzepi, widely recognized as the world's greatest chef, at a pivotal point in both the chef's career (shutting down his frighteningly famous restaurant to embark on a Quixotic new one) and the author's life (marital meltdown, new love). What results is a study of the rawness of pursuit and a treatise on the virtues of saying, "What the hell, why not?", breaking things, and never-ever-ever standing still. Also, tortillas. –Jonathan Segura, V-P, executive editor

In the Night of Memory by Linda LeGarde Grover

Linda LeGarde Grover is literary Minnesota’s best-kept secret. I first encountered Grover shortly after I moved to the state 25 years ago, and have been a loyal fan of hers ever since. In the Night of Memory continues the story of the Gallette family and their relatives and friends on the (fictional) Mozhay Point Reservation outside of Duluth whom I met in The Dancing Boots and The Road to Sweetgrass. In the Night of Memory follows two little Ojibwe girls, Azure Sky and Rain Dawn, who are taken by county social services from their mother, Loretta, an alcoholic ne’er-do-well who then disappears, never to be seen again. But this novel is more than another sad tale about lost children trying to make their way home after their family is torn apart: Grover explores the impact of Loretta’s disappearance upon those who had known her and their determination to rescue Azure and Rain from the foster care system and return them to their mother’s tribe. Like Louise Erdrich, another of my favorite novelists, Grover does a superb job weaving together past and present, myth, legend, and history to tell a compelling story that illuminates the simmering tensions between Native and European-American cultures that persist in this country. –Claire Kirch, midwest correspondent

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

I often prefer to wait to read big books until long after publication, so I can judge for myself without feeling pressured. But the bookseller buzz for Ocean Vuong, who had already established himself as an award-winning poet, was so strong that I had to read his debut novel when it first came out. The writing in the book is so gorgeous that I took a little too much time to savor it, until a friend advised, “Read it fast. Then read it again.” On its face this semi-autobiographical novel tells the story of Little Dog, his mother, and his grandmother, how they came to America and how he knew he wanted to become a writer as early as the third grade after reading Patricia Polacco’s Thunder Cake, which “pulled [him] deeper into the current of language.” The novel’s other concerns are with war, violence, and love in its many complexities, including Little Dog’s physical love for Trevor. “Memory is a choice,” Little Dog reminds his mother that she told him, “with your back to me, the way a god would say it.” The memories that Vuong has chosen to recount and embellish here add up to a powerful whole. –Judith Rosen, contributing editor

The Peanuts Papers: Writers and Cartoonists on Charlie Brown, Snoopy & the Gang, and the Meaning of Life edited by Andrew Blauner

As a Peanuts fan, I relished the appreciations in this tribute anthology from such notables as Adam Gopnik, Ann Patchett, Mona Simpson, Rick Moody, Jonathan Franzen, and Jennifer Finney Boylan. The best of the pieces elegantly combine personal reflections with commentary on the impact of Charles M. Schulz’s iconic cartoon strip. I was pleased to see that a few contributors weren’t afraid to address the strip’s decline, notably Bruce Handy, who points out that in its later decades it became “cute and self-conscious.” I look forward to the day when Peanuts goes out of copyright and at last someone can write a critical study of Schulz’s opus that reprints individual strips to illustrate its virtues and faults, just as Lucy van Pelt once delivered a comprehensive survey of Charlie Brown’s faults to Charlie Brown with visual aids. –Peter Cannon, senior editor

Rabbits for Food by Binnie Kirshenbaum

I saw the ARC on the desk of more than one coworker and couldn’t get enough of the cover, and the wary-looking rabbit crouched under the blunt, flesh-hungry title. Inside, the plot follows the descent of Bunny, an acerbic novelist whose clinical depression lands her in what she calls the psycho ward. Divided into two parts, before and during Bunny’s hospitalization, the novel’s narration is punctuated by essays she writes in response to therapy-sanctioned prompts. When she concludes one with, “People who are not easy to like, they have feelings just like nice people do,” it reads as observational, even empathetic, rather than self-pitying, a notable distinction in a character who’s been engaging in some seriously self-destructive behavior. Kirshenbaum writes with astonishing precision, and at the end, when it’s unclear where Bunny’s story might lead, she absolutely sticks the landing. –Carolyn Juris, features editor

A Song for a New Day by Sarah Pinsker

It's very hard to choose, but I think the one that will stay with me is Sarah Pinsker's A Song for a New Day. This is Pinsker's first novel, but you wouldn't know it from the rich prose and perfect plotting. What I love most is that she doesn't look for simple answers: it's a post-apocalyptic novel full of as much optimism as grief (and surprisingly little fear), an examination of the music industry that holds space for both musicians who choose to stay raw and niche and those who sacrifice some edginess for financial success and broader reach. I saw the book on display in a radical bookstore the other day and was so pleased to see that its political messages are being recognized as such. These days, Pinsker's emphasis on hope, grassroots action, and the ability of individuals to create positive change feel as radical as any manifesto. I want this book to drag us all into a better future. (Full disclosure: I published one of Pinsker's short stories in an anthology years ago, and we're friendly acquaintances. But I'd be recommending her novel to everyone regardless.) –Rose Fox, director of BookLife reviews

Sweet Days of Discipline by Fleur Jaeggy

There are a lot of things I'm going to miss now that Gabe Habash isn't PW's fiction editor, and book recommendations are one of them. He suggested I read the Swiss author Fleur Jaeggy last year, and like a fool I dallied. This year, I made up for it by devouring every jagged little clause of Jaeggy's translated into English from the original Italian. It's all brilliant, but Sweet Days of Discipline, about a young probable sociopath at a Swiss all-girls boarding school falling, in her own eerie way, for her best friend, really rearranged my insides. –John Maher, news and digital editor

The Topeka School by Ben Lerner

A number of novels have come out in recent years with a promise of having something to say about the American interior, whether through stories of opioid addiction, combat veterans, the rise of populism, or all of the above. Some have been quite good, while others have fallen well short of the Great American Novel status they seemed to aim for. Perhaps part of what makes Lerner’s third novel work so well, despite a cover that screams “IMPORTANT” and calls to mind DeLillo’s White Noise, is the choice to set the book in the recent past, allowing him to apply his infectious brand of near-autofiction to a territory remote from the settings of his previous work: Topeka, Kans., the town where he grew up. In a story of high school competitive speech, ranging from forensics tournaments to drunken white-boy freestyle battles, Lerner locates the tension that can make young men turn on each other, setting the stage for some to soar and others to be stomped into the cracks. As the chapters alternate between high school senior Adam Gordon; his parents, Jane and Jonathan; and Jonathan’s therapy patient Darren, Lerner reads like a better-adjusted, more confident David Foster Wallace, similarly influenced by DeLillo and brimming with intelligence and empathy. –David Varno, reviews editor