It's Oscar season! And while the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences makes no bones about its foremost love being for the cinematic arts, each year's Oscar nods clearly indicate how deeply beholden the film business is to the business of books. To illustrate the point, we've rounded up our reviews of the books adapted into, or inspiring, this year's Academy Award–nominated films, from Oppenheimer and Nyad to American Fiction and The Boy and the Heron.

Editor's Note: These historical reviews, including those sourced from our digital archive, are presented in the varying editorial styles in which they originally appeared over the past five decades in Publishers Weekly.

American Prometheus: The Triump and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Oppenheimer, Best Picture)

Though many recognize Oppenheimer (1904–1967) as the father of the atomic bomb, few are as familiar with his career before and after Los Alamos. Sherwin (A World Destroyed ) has spent 25 years researching every facet of Oppenheimer's life, from his childhood on Manhattan's Upper West Side and his prewar years as a Berkeley physicist to his public humiliation when he was branded a security risk at the height of anticommunist hysteria in 1954. Teaming up with Bird, an acclaimed Cold War historian (The Color of Truth ), Sherwin examines the evidence surrounding Oppenheimer's "hazy and vague" connections to the Communist Party in the 1930s—loose interactions consistent with the activities of contemporary progressives. But those politics, in combination with Oppenheimer's abrasive personality, were enough for conservatives, from fellow scientist Edward Teller to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, to work at destroying Oppenheimer's postwar reputation and prevent him from swaying public opinion against the development of a hydrogen bomb. Bird and Sherwin identify Atomic Energy Commission head Lewis Strauss as the ringleader of a "conspiracy" that culminated in a security clearance hearing designed as a "show trial." Strauss's tactics included illegal wiretaps of Oppenheimer's attorney; those transcripts and other government documents are invaluable in debunking the charges against Oppenheimer. The political drama is enhanced by the close attention to Oppenheimer's personal life, and Bird and Sherwin do not conceal their occasional frustration with his arrogant stonewalling and panicky blunders, even as they shed light on the psychological roots for those failures, restoring human complexity to a man who had been both elevated and demonized. 32 pages of photos not seen by PW. (Apr. 10)

Poor Things: Episodes from the Early Life of Archibald McCandless M.D., Scottish Public Health Officer (Poor Things, Best Picture)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI (Killers of the Flower Moon, Best Picture)

Erasure (American Fiction, Best Picture)

Everett's (Glyph; Frenzy; etc.) latest is an over-the-top masterpiece about an African-American writer who "overcomes" his intellectual tendency to "write white" and ends up penning a parody of ghetto fiction that becomes a huge commercial and literary success. Thelonius "Monk" Ellison is an erudite, accomplished but seldom-read author who insists on writing obscure literary papers rather than the so-called "ghetto prose" that would make him a commercial success. He finally succumbs to temptation after seeing the Oberlin-educated author of We's Lives in da Ghetto during her appearance on a talk show, firing back with a parody called My Pafology, which he submits to his startled agent under the gangsta pseudonym of Stagg R. Leigh. Ellison quickly finds himself with a six-figure advance from a major house, a multimillion-dollar offer for the movie rights and a monster bestseller on his hands. The money helps with a family crisis, allowing Ellison to care for his widowed mother as she drifts into the fog of Alzheimer's, but it doesn't ease the pain after his sister, a physician, is shot by right-wing fanatics for performing abortions. The dark side of wealth surfaces when both the movie mogul and talk-show host demand to meet the nonexistent Leigh, forcing Ellison to don a disguise and invent a sullen, enigmatic character to meet the demands of the market. The final indignity occurs when Ellison becomes a judge for a major book award and My Pafology (title changed to Fuck) gets nominated, forcing the author to come to terms with his perverse literary joke. Percival's talent is multifaceted, sparked by a satiric brilliance that could place him alongside Wright and Ellison as he skewers the conventions of racial and political correctness. (Sept. 21)

Forecast: Everett has been well-reviewed before, but his latest far surpasses his previous efforts. Passionate word of mouth (of which there should be plenty), rave reviews (ditto) and the startling cover (a young, smiling black boy holding a toy gun to his head) could help turn this into a genuine publishing event.

The Zone of Interest (The Zone of Interest, Best Picture)

Find a Way: One Wild and Precious Life (Nyad, Best Actress)

The Color Purple (The Color Purple, Best Supporting Actress)

Alice Walker's first novel since Meridian is a stunning, brilliantly conceived book about two black Southern women, sisters who are separated at adolescence and for the next 30 years never forsake their devotion to each other. Their stories are principally told in the letters of the elder sister, Celie. Written in a rich dialogue, though barely literate, they are addressed to God because Celie doesn't know where her sister Nettie is. In these letters, Celie recounts her pained life as part of the lowest caste in society—a poor, unattractive, uneducated, Southern black woman. Raped by a man she thinks is her father, then robbed of her two children, Celie is later given to a man as a wife. The love in Celie's life is Nettie who has gone to Africa with the black missionary couple who have unknowingly adopted Celie's children. Nettie's letters to Celie are kept by Celie's husband. But Celie finds another love in an extraordinary woman, Shug Avery, a singer who comes to live with Celie's husband. Through Shug, Celie begins to feel loved and valued for the first time in her life. Spanning some 30 years, this is a saga filled with joy and pain, humor and bitterness, and an array of characters who live, breathe, and illuminate the world of these black women.

Editor's Note: This review was published in the May 14, 1982 issue of Publishers Weekly.

more

How Do You Live? (The Boy and the Heron, Best Animated Feature Film)

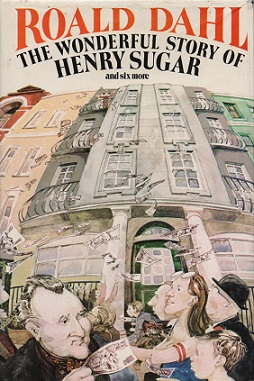

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Six More (The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar, Best Live-Action Short Film)

Few modern writers have attracted such an appreciative audience among adults and children as Dahl. His Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has been a hit with boys and girls for years. They will welcome the short stories in his latest collection, a book which includes the author's factual account of how he became an author and his first story, "A Piece of Cake." The latter is an astonishingly convincing fiction describing the hallucinations of a British flyer, shot down during World War II. "The Hitchhiker" tells the funny talke of a motorist who picks up a fellow who turns out to be an adroit pickpocket, stealing everything removable from the driver without giving himself away but paying for his ride in a hilarious way. All the tales are entrancing inventions.

Editor's Note: This review was published in the October 31, 1977 issue of Publishers Weekly.

more

Nimona (Nimona, Best Animated Feature Film)

Robot Dreams (Robot Dreams, Best Animated Feature Film)

Robots, ducks, melting snowmen and other mute creatures, all rendered in sweet and simple drawings, go through some very big, very human ordeals in Varon's (Chicken and Cat ) elegiac and lovely graphic novel about friendship. Dog buys a build-your-own-robot kit and assembles a new best friend for himself. But a day at the beach leaves Robot's joints rusted and immobile, and Dog is obliged to abandon him there. While Dog spends the next year trying to fill the hole in his life left by Robot—and assuage his guilt—Robot lies inert on the beach, dreaming of rescue and escape. Dog's episodic stories are particularly poignant in the way they mirror the human tendency to “try things out” in the hopes of meeting some emotional need; Robot is an avatar for all children who wonder why they aren't receiving the love they think they deserve. In a conclusion both powerful and original, Robot ends up reworked into a radio by a raccoon grateful for the music, and forgives Dog, even if Dog doesn't realize it; for once characters don't have to wind up back together to find happiness. Tender, funny and wise. Ages 8-up. (Aug.)